From the Diary of H.M. the Shah of Persia

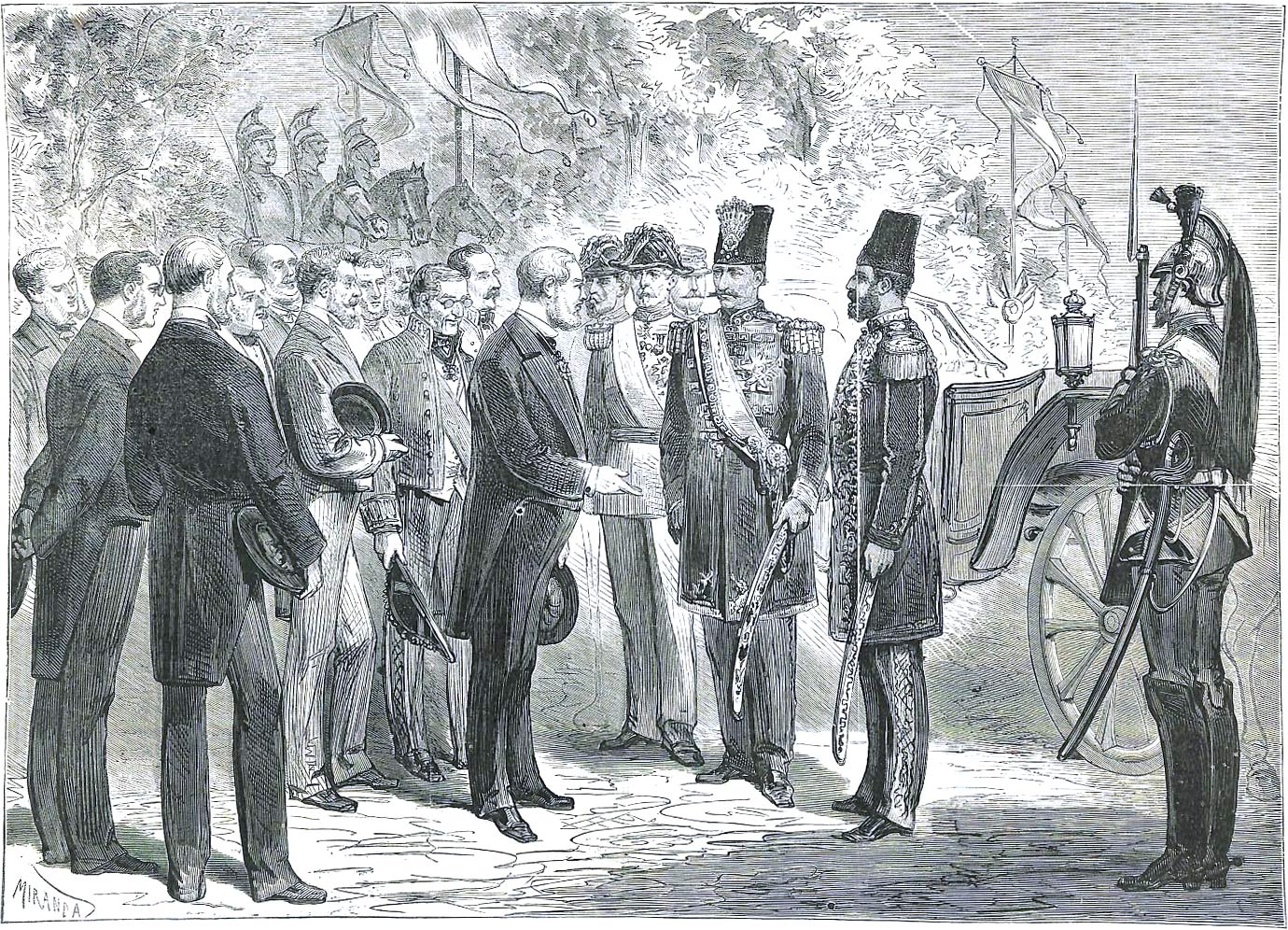

“We rose early in the morning, went down into a boat, and pushed off for the shore,” says Naser al-Din Shah—a.k.a. the Shah of Persia—in his travelogue, recalling his arrival in Paris on July 6, 1873. It was indeed a reception filled with pomp and ceremony befitting a sovereign.

They all shouted: “Vive le Schah de Perse” and “Vive la France”…and they had prepared a beautiful illumination. In all the streets they had suspended crystal lamps like round globes; but the wind somewhat interfered with these…. A very pretty and choice triumphal arch had been erected also, of flowers and shrubs, bunches of flowers, chandeliers and the like, various devices with weapons—such as pistols, muskets, lance-heads. In truth, they had displayed talent.

At night, the Shah and his entourage, which consisted of almost his entire government after he had entrusted matters of state in Tehran to his son, ambled through the streets of Paris. In his travelogue, he describes a scene that is not too different from a modern-day stroll through Paris, save for electricity.

The lamps of the city are all illuminated with gas; so that it is a very bright, beautiful, and charming city. Numbers of people were seated in carriages and driving about; or, seated in the cafes and similar places, were enjoying themselves.

He visited botanical gardens, palaces, and the Victorian-era zoos that were becoming popular at the time, replete with flora and fauna from exotic and newly conquered places. Of all things to make an impression on the king of Persia was none other than the Kangaroo! He found the strange animal to be very “similar to the jerboa”—a small bouncing rodent endemic in the East.

At one point, the Shah of Persia met a Rothschild, “a Jew who is exceedingly rich,” as he recalls in his travelogue. He went on to document their amusingly prescient conversation.

[Rothschild] greatly advocated the cause of the Jews, mentioned the Jews of Persia, and claimed tranquillity for them. I said to him: “I have heard that you, brothers, possess a thousand crores of money. I consider the best thing to do would be that you should pay fifty crores to some large or small State, and buy a territory in which you could collect all the Jews of the whole world, you becoming their chiefs, and leading them on their way in peace so that you should no longer be thus scattered and dispersed.” We laughed heartily, and he made no reply. I gave him an assurance that I do protect every alien nationality that is in Persia.

Particularly noteworthy about the impressions of the Persian king in a foreign land was how he perceived the seeds of revolution that was defining much of Europe at that time. He writes about “the mayhem of Communes,” and how the people were split three ways in their preference for a monarchy.

The city of Paris is now, in reality, the property of the peasantry and common people, who do whatever they like, as the Government has no adequate means of repression. The palace of the Tuileries, which was the finest building in the world, is now a mass of ruins, as the men of the Commune set fire to it. Nothing remains of the palace but its walls. We were sadly grieved for this; but, thanks be to God, the palace of the Louvre, which adjoins that of the Tuileries, has been saved and is not destroyed.

He takes note of the French—the “women and men,” as he refers to them—observing that they are “small made and attenuated of limb,” nothing like the inhabitants of Russia, Germany, and England, the places he had already seen. The French, he concludes, “more resemble the people of the East.”

Apparently claustrophobic, he writes of “holes in mountains,” a reference to railroad tunnels. He describes traveling through them as a “suffocating kind of sensation about the heart.”

But there is no mistaking that the King of Persia found a natural affinity with the jewel of Europe.

Paris is a beautiful and graceful city, with a delicious climate. It generally enjoys sunshine, thus much resembling the climate of Persia.