The streets opposite the University of Tehran, leading to Revolution Square, are the capital’s bookstore district. The shops on the main avenue cater to customers looking for new publications, while tucked away from view in back alleys or on the upper floors of old-fashioned, narrow shopping passages, rare-book stores offer a portal into a bygone time. On the northern side of the square, behind a falafel shop and taxi drivers hollering their destinations to passersby, a tiny shop specializes in art books, theater brochures, and gallery catalogues from prerevolutionary Iran.

Three customers can fit inside if none of them makes any sudden move. In the middle of the floor-to-wall stacks of books, a gas heater perilously close to both customers and age-dried pages fights the cold winter air that rushes through the sliding door each time a customer shuffles in. The owner, Soheil Dehkordi, stands barricaded behind a desk covered with more books.

A man comes in asking for a book of poetry and Dehkordi vaguely waves him in the right direction without lifting his glance from a special customer, the owner of a photo gallery in north Tehran, who is collecting Iranian photobooks for her gallery’s library. Today she is looking for a set of what were originally five books from the 1980s titled The Imposed War: Defense vs. Aggression about Iran’s conflict with its neighbor Iraq, produced by the national War Propaganda Council. “There was a time when these books had no takers and you could find them cheap here and there, especially in the provinces,” says Dehkordi. “Now suddenly there are more people asking for them. And even the provincial shops say they have their own buyers.”

The transformation of these books over the past 35 years, from unapologetic tools of propaganda to collectible objects sought by art aficionados, traces a change in the nature of remembering the war, which lasted almost a decade and caused as many as 600,000 deaths in Iran. From the start of the Islamic Republic to today, the fate of the photobooks, which include graphic photographs of death and injury, reflects judgments about the visual history of the regime as it established itself, consolidated its power, and, for the past decade or more, as it has faced internal rumblings from its citizens. Following the trail of the photobooks also provides a view of the circumstances that spurred the growth of documentary photography in Iran, as the state worked to monopolize and control the country’s visual culture.

In a symbiotic relationship, photography has helped make and maintain the Islamists’ vision of the Revolution in Iran, and the Revolution helped push the boundaries of documentary photography in the country. The Revolution, followed by the taking of American hostages and then the eight-year war with Iraq, propelled Iranian photographers into the fray, transforming them into serious practitioners of new genres.

By the time of the Revolution in the late 1970s, Iranians had been exposed to photography for nearly 100 years; it wasn’t uncommon for ordinary middle-class people to own cameras. An established cadre of photojournalists followed the royal court and provided news photographs for the daily newspapers and numerous weekly magazines, while Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi employed foreign photographers to produce glossy coffee-table books celebrating the glories of Persian culture.

The Revolution that toppled the Shah relied on this photographic technology, just as it employed other late 20th-century technologies to advance its cause. Ayatollah Khomeini’s doctrine had been smuggled into the country on cassettes that were reproduced for furtive circulation. Media-savvy revolutionaries also recognized the power of images, and even invited Western photographers to travel on the airplane for Khomeini’s triumphant flight back to Iran.

Media anthropologist Roxanna Varzi of the University of California, Irvine, argues that the Islamists expertly exploited the value of images in creating an identity for the new state. “Almost every mural, stamp, and piece of currency produced graphically and in painting derives its image from a photograph that is doctored to create a billboard, poster or postage stamp,” she writes in Warring Souls: Youth, Media and Martyrdom in Post-Revolution Iran. Photography was becoming one of the most useful instruments in the Islamic Republic’s toolbox.

Photos published daily in newspapers helped fix the inevitability of a new Iran in the eyes of the world and the psyche of the Iranian nation: Ayatollah Khomeini sitting under an apple tree in exile in France, his descending the steps of the Air France aircraft that carried him back to Tehran, the crying Shah leaving the country, executed generals’ and ministers’ corpses lying naked on mortuary slabs. Such images forged the country’s collective memory. Ever since, the regime has continued to shape that memory—often through photographs.

❧

When Maryam Zandi heard about the protest march, she had to go out to see it for herself. National Iranian Radio and Television, where she was a staff photographer, was on strike in sympathy with the anti-Shah uprising of 1978 and she was at home. These were strange new times, she thought, and they had to be recorded. There was no one to look after her two-year-old daughter. So she threw her camera bag on her shoulder and her baby girl on her hip, and headed out.

Crowds already filled the streets and the square around the University of Tehran, punching their fists in the air, shouting slogans against the Shah and dictatorship. Zandi decided to climb upon a bus shelter to get a better view, but couldn’t do so while holding her daughter in her arms. She asked a woman standing nearby if she would hold her child for a little while. “On one condition,” said the woman. “If you shout, ‘Long live Khomeini.’” Zandi passed the child into the stranger’s arms and yelled, “Of course, long live Khomeini!” as she climbed atop the shelter. She doesn’t remember how long she stayed there, but she does remember being scared when she saw the crowd from above. She had never seen so many people in one place.

The more than one million people who came onto the streets of Tehran that day demanding change created the turning point in the fortunes of the Shah and the country. It was Monday, December 11, 1978, the day of Ashura, the second of two consecutive holy days of mourning. On Ashura, processions of black-clad men take over the streets of the capital to mark the martyrdom of Imam Hussein, one of Iran’s holiest saints, by flagellating themselves with chains to the sounds of beating drums. The revolutionaries, well aware of the immense symbolism of these days, had called their second march for the mourning period. The Shah had ordered the army to stand down in respect for the religious ritual.

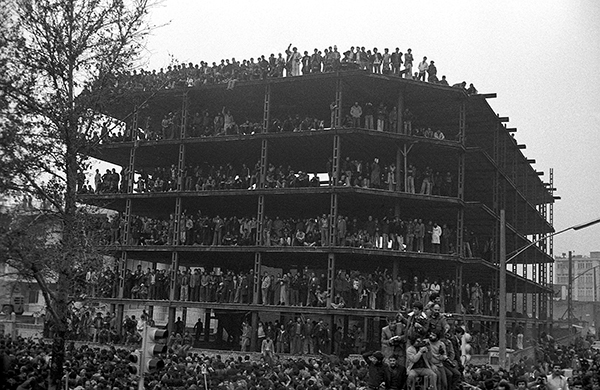

Numerous photographs of the Ashura demonstrations show the multitudes marching with their banners. But two of the most memorable images of that day depict a half-finished five-story building overrun by onlookers seeking the perfect vantage point. Filling every floor, men and women flesh out the spaces where walls should have been. Two photographers captured that scene, the Iranian Bahman Jalali and the Frenchman Michel Setboun, who was in Iran to cover the events for the Paris-based agency SIPA. Mere minutes separate Jalali and Setboun’s images, but the atmospheres captured through their viewfinders differ considerably. In Jalali’s photo, the crowd at street level seems to be waiting for the action to begin. In the right of this image, a cluster of photographers perches precariously on a platform facing the tree-lined boulevard where the march is approaching—a testament to the number of photographers on Tehran’s streets those decisive days. In Setboun’s more animated image, people are more clearly engaged with the scene in front of them. Some wave their fists in the air in support of the marchers, who seem to be close by.

In both cases, shot from a middle distance, the photographs of the half-finished building on the corner of Khosh Street close to the Azadi Tower suggest a striking metaphor: the country’s incomplete project of modernity. The photos are even more searing as a symbol of the Revolution: tiers of people, hopeful and excited, with merely a skeletal idea of what they want. None of them knows how this half-finished structure will look when the project is complete.

Bahman Jalali wasn’t a photographer by training. Before the Revolution, he had studied politics and economics at the University of Tehran. He traveled with the architecture students on their many road trips around Iran, taking photos of traditional houses. After graduation, his hobby became his profession; beginning in the early 1970s, he worked as a photographer for Tamasha, the magazine of National Iranian Radio and Television. When the unrest began in 1978, he and his wife, Rana Javadi, who had picked up the photography bug from him, joined the throngs in the streets to photograph the events. She moved freely among the women and provided a different point of view.

Setboun, an architect by training, had come to Iran in May 1978, almost too early, looking for a subject and sensing that something was about to happen. “Remember this was only ten years after the events of May 1968. Only [a few] years after the end of Vietnam. This was my chance to be part of something that I had missed,” he says. He ended up with time to get to know the country and its people and to record Iranian life at an important juncture in great detail, from the poorer sections of southern Tehran to Turkeman fishermen and all the way to photographs of royal birthdays at the court. His extensive travels around the country in the monarchy’s final year made him a street expert on Iran’s finer social cracks.

After the victory of the Revolution, Iran experienced a euphoric atmosphere of freedom. The Shah’s system of censorship had disappeared, and the Islamic Republic’s was not yet set up. Jalali exhibited his photographs of the street protests at Tehran’s Farabi University, an institution created by the Shah’s wife, Farah, in the image of Les Beaux Arts de Paris. (Under the Islamic regime, it would be amalgamated into the Tehran University of Art with two other schools.) Seeing the exhibit, Karim Emami, who had just been removed as head of Sorush Publications at National Iranian Television, suggested that Jalali publish a book of images documenting the Revolution. People like Emami, who had been educated in the West and had worked as managers in the Shah’s regime, were not regarded as loyal to the Revolution’s Islamic ideals and were purged en masse. Jalali was also at loose ends as Tamasha was in limbo during the changeover. Along with his wife, Goli—purged as the head librarian of Farabi University—Emami set up a shoestring publishing house called Zamineh from their home, specifically to publish Jalali’s photos.

Days of Blood, Days of Fire was published in June 1979, only four months after the conclusion of the Revolution, under Jalali’s name. The publishers also used photos by Jalali’s wife, Javadi, and a handful of friends to fill the gaps in the narrative. The book is likely Iran’s first documentary photobook depicting the turbulence of the Revolution—and it is an artistically experimental one as well. Instead of captions, Emami accompanied the photos with popular slogans of the Revolution and quotes from landmark speeches by the leaders of the uprising. This creative book gave the reader not just visuals, but also a sample of the sounds of those tumultuous times. Emami already had an eye on the historical record, Goli recounts, predicting that some years later, “people will want to know on what basis and slogans this Revolution happened.” Instead of using high-gloss paper, Emami chose an inexpensive thick paper that made the images look grainy and kept the book affordable at about 170 rials (US$2.50). To this day, it holds the record for the highest-selling book of its genre. The book’s first print run of 22,000 copies was sold out within a handful of weeks, so a second run of 15,000 copies followed.

Around the same time as Jalali’s publication, Kaveh Golestan, who had begun his career as a photojournalist in Belfast in the early 1970s, self-published Uprising, a photobook presenting his chronicle of the days of the Revolution. He printed 2,000 copies and sold them outside the University of Tehran in the impromptu book bazaar that popped up during the censorship vacuum, when books that had been banned for 30 years were printed and sold next to revolutionary tracts and pamphlets in an intellectual free market. Clearly, Golestan, Jalali, and their colleagues recognized a tremendous rupture in the history of their country that warranted such speedy production of records that would be more permanent than newspapers.

Meanwhile, in Europe, Michel Setboun just as quickly created his own photobook based on the year-long assignment that he credits with making him a photojournalist: Iran: L’eclatement (The eruption), published by Le Sycamore in September 1979. The range of photos suggests that Setboun was everywhere, from the Shah’s palace to the transitional government’s meeting with Yasser Arafat to recording the armed revolutionaries and the street protests. In the last chapter, titled “La fête est finie” (The party’s over), he calls the Ayatollah’s Islamic Republic “a monstrosity of intolerance and stupidity” and predicts that “Iran will not sing, not laugh, not rhyme, not love, but pray and obey the barking of the Guardian of the Revolution.” He wonders what will happen to the minorities he photographed, as if anticipating the uprising by the Kurds, who were dealt with punitively by the new Islamic government from the start. His images of armed groups in the streets include a photograph of a young woman guerilla fighter in combat trousers, loading her weapon, with a cigarette in her mouth and no hejab on her head.

Setboun could afford to include such comments and images in a book distributed in Europe, but soon, inside Iran, the far more modest material in Jalali’s book began to seem risky to its own producers. Among its many images, the book depicted members of the Mojahedin-e Khalgh (MEK), a group that had participated in the Revolution, but had fallen afoul of the faction supporting Khomeini. It also contained photographs of women protesters from all walks of life, many of them without hejab—which, within months of the Revolution, Khomeini had insisted that women wear. (His “recommendation” acquired the full force of law in 1983.) Loath to set themselves up for censorship, the Emamis decided not to pursue a permit for a third print run for Jalali’s book. In fact, having published seven books, including a second photobook by Jalali, they shut down their press altogether.

The Revolution had provided a fertile ground for photojournalists—both Iranians, who were learning how to photograph a conflict for the first time on their home turf, and for experienced photographers working for foreign media. Both groups produced compelling work. And the Islamic regime was beginning to control the use of images to tell the story they wanted to project.

❧

On November 4, 1979, another event propelled the growth of homegrown photojournalism and created a new opportunity for the regime to use visual media to convey its independence from the West and, specifically, its anger toward the United States (already deemed “the Great Satan”), which had propped up the Shah: A group of hardline students supporting Ayatollah Khomeini climbed over the walls of the US embassy compound in Tehran and took 52 American diplomats and citizens hostage for 444 days. They paraded the hostages, blindfolded, with arms tied, to be photographed by the international press. As Amy Lyford, an art historian specializing in photography, writes: “These students understood the media’s power to disseminate information, and they took full advantage of this to broadcast their activities to the world: they distributed photographs, held news conferences, and made the hostages they had taken, visually available to the press surrounding the embassy.”

One such image became the logo for the US television news program Nightline, created to follow the hostage crisis on a nightly basis: Behind anchor Ted Koppel’s left shoulder, a screen shows a yellow map of Iran ripped out of geographic context, floating against a black background without neighboring countries. To the map’s right is a photo of a man—a hostage—in a white shirt, and a thick white blindfold wrapped in layer after layer around his head. It looks as though he is being readied for execution.

After the embassy invasion and hostage-taking, many foreign journalists, including Setboun, left Iran, and the job of covering the still volatile country fell to locals who stepped in to supply the foreign media with the images they needed. Setboun handed his SIPA mantle to Reza Deghati, whom he connected to the agency. “There were these young Iranian photographers that grew up with us. It was time to let them take over. They could speak the language; all they needed was a connection to the outside media, which they didn’t have before,” he says. The hostage-taking was not just good for Iranian local photographers, it was also one of the landmark events that consolidated the Islamists’ hold on the country and its future. Iran’s foreign policy took an irreversible turn into isolationism and belligerence toward the world. And it tightened its grip internally.

Maryam Zandi continued to take photographs in Tehran’s streets until 1980. The revolutionary overseers known as the Komiteh were working, among other things, to control the story of the Revolution and define it as wholly Islamic, despite the other groups—communists, nationalists—that had participated in ousting the Shah. “If they felt that you were taking photos in support of the wrong group, they would follow and harass or even beat the photographer,” Zandi recalls. The Komiteh wielded batons. “I saw some scuffles,” she says, and they confiscated her cameras a couple of times. Aside from being stifled by the Islamists, photographers could also get caught in the crossfire between the Khomeinists and other armed revolutionary groups vying for power. Zandi decided it was not worth the trouble—she turned to portraiture.

On September 20, 1980, less than 18 months after the departure of the Shah, Saddam Hussein attacked and eventually occupied the southern city of Khorramshahr on Iran’s border with Iraq, provoking a war that lasted nearly a decade. Often compared to World War I for its extensive trench warfare, the use of chemical weapons, and the horrendous loss of life and capital, the Iran-Iraq War also resembles the earlier conflict in the role photography played in shaping public attitudes toward the event.

“The revolution brought out a multiplicity of voices, at times emphasizing contradictory aspirations,” writes Farideh Farhi, a political scientist at the University of Hawaii. “The war offered a univocal venue for both crushing domestic opposition to the newly emerging political order as well as ‘Sacred Defense’ against international aggression.” It also gave Jalali and his colleagues the opportunity to pursue another genre new to them: war photography. Hundreds of photographers ended up documenting the war.

Some worked for official entities like IRNA (the Islamic Republic News Agency, formerly called Pars), national television, and the daily newspapers, all controlled by the state. Another group worked for Western media and were given limited access to the front. A third were volunteer soldiers who learned the craft and became photographers at the front, covering not just the battles, but also the daily lives of the soldiers. A fourth group, a special unit of 40 young men, were recruited through two mosques in the southern province of Khuzestan, home to Iran’s oil fields and where the main fighting took place. Each was given a still camera, a 16mm film camera, and a motorbike with which to roam the front and record the war. In addition, the various sections of the armed forces had their own photographic units, and some individual soldiers took photographs for personal use as mementos.

When war broke out, Ali Fereydouni was working as an assistant in the IRNA laboratory developing and printing other people’s photographs. When one of the agency’s photographers refused to go to the front to cover the conflict, Fereydouni volunteered; he supported the Revolution and the war. The agency gave him a hefty Hasselblad camera imported specially from Germany for the lavish, infamous party the Shah had put on in 1971 for heads of state from around the world at the Persepolis ruins, celebrating 2,500 years of monarchy in Iran since Cyrus the Great. Now that Hasselblad was in the hands of a revolutionary sympathizer at the war front, but Fereydouni had to be economical with his shots. His medium-format camera took rolls of only 12 frames and there was a scarcity of film; he had to learn about light and how to use it in the middle of a battlefield.

Fereydouni’s photographs, featuring noble soldiers, differ from those by photographers like Jalali, who was independent and, with an artistic eye, took pictures of the devastation of the war from behind the lines, or Golestan, who sent news images to the foreign press from the battle front that he visited intermittently. Their circumstances differed as well. Whereas Fereydouni and his ilk were the equivalent of embedded photographers, the men who sent their work overseas were not living the war at the front, like Fereydouni and those ideologically connected to it. While the foreigners had access to all the film they wanted and were paid substantial fees in dollars, what they didn’t have was the free access afforded to the state-sanctioned photographers. They had to secure permits to go to the front and those often entailed multiple bureaucratic hurdles.

In the summer of 1981, as the war raged, the Ministry of Islamic Guidance along with the Museum of Contemporary Art published a photobook that recounted the Revolution and began to fix its history in the regime’s preferred narrative. The cover of the square tome, titled Images: The Islamic Revolution of Iran, has a striking design in black, white, and red. It shows a blood-red handprint on a white background, and then superimposed on top of that, a negative of the same image: a white hand on a bloody background bordered by the sprockets of a roll of film. While the design echoes the graphics of the Shah’s time—the Islamic Republic hadn’t developed an aesthetic yet—in content, it expresses the regime’s entry into the cultural arena as a space for asserting its power. The design evokes the idea of martyrdom, refers to common revolutionary images of protesters with hands bloodied by their fallen comrades, and calls to mind the Shia symbol of the five saints—all linked through the representative medium of photography.

In the book’s preface, the publishers opine (in English) about the misrepresentation of the Revolution by the imperialist Western media: “Most probably no transformation has consciously been so badly introduced from the point of the media of the world as the Revolution of Iran.” Despite its title, the book also includes images of the war, which it tacitly links to the Revolution.

Being in charge of the apparatus that controls the way historical events are remembered and told is an essential part of nation-building and vital to a new system of governance like the Islamic Republic. Shaping collective memory, scholars of nationalism agree, is essential to national identity. Duncan Bell of Cambridge University refines the notion of collective memory, arguing in “Mythscapes: Memory, Mythology, and the National Identity” that memory is intrinsically the property of individual minds and that what states create, through a ritualistic narrative of events, should more correctly be called mythology. “Myth,” he writes, “serves to flatten the complexity, the nuance, the performative contradictions of human history; it presents instead a simplistic and often univocal story.”

The Islamic Republic has interwoven two myths—one of the Revolution, the other of the long war—in the Iranian mindset. Iranians had hardly processed the effects of the Revolution when the war began. Along with photobooks like Images, the state-sponsored propaganda effort produced new cultural material in every medium available to promote the ideals of the Revolution and, soon after, the righteousness of the Iraqi conflict, which it referred to as the “Imposed War” or the “Sacred Defense.” Documentary films brought the war front to Iranian front rooms. Music intended to rouse the fighting spirit of the nation permeated the airwaves. A new genre of war cinema emerged and city walls transformed into a giant showcase of martyrdom—murals of men, both the old heroes of the Revolution and the young who perished in the war.

As part of these efforts to cement the Islamic Republic’s origin myth, in 1981 Iran’s official news agency, IRNA, established an archive of the reign of the Shah and the Revolution, and recruited a young photographer, Seifollah Samadian, to organize it—in the process, saving more than one million frames of negatives from the Shah’s reign from militants who wanted to destroy them. As described by scholars Joan Schwartz and Terry Cook, archives are a tool of power—“power over memory and identity, over the fundamental ways in which society seeks evidence of what its core values are and have been, where it has come from and where it is going.” What’s more, they write, it’s the “power of the present to control what the future will remember of the past.” In his new post, Samadian was archiving photographs that agency photographers were submitting from the war front—including those by Fereydouni, who had shot 25,000 frames by war’s end.

In May 1982, Khorramshahr was recaptured by Iranian troops after a savage battle that gave it the nickname Khooninshahr (city of blood). Saddam withdrew his troops and indicated he was ready to end the conflict. Believing that the war was just about over, Samadian (today the publisher of Iran’s only photography annual, Tassvir) suggested that a book be produced to showcase the atrocities committed against Iran. Samadian and Mahmoud Kalari, now a celebrated cinematographer, collected pictures by professional and amateur soldier-photographers for what would become the first volume of The Imposed War: Defense vs. Aggression. Morteza Momayez, recognized as the father of Iranian graphic design, laid it out. The coffee-table book was printed in Germany to ensure a level of technical quality not then available in Iran.

Produced by the War Propaganda Council, the photobook was taken to the UN as part of Iran’s case against Iraq. Its success paved the way for more books to follow as the war, unexpectedly, continued. “No one in their right minds would produce a photobook about an ongoing war,” Samadian says. But that is exactly what he ended up doing for the next five years, as the regime, as a matter of policy, extended the conflict. Samadian put together photobooks on various themes of the war to coincide with the anniversary of the Islamic Republic’s inception, one a year until the war’s end in 1988.

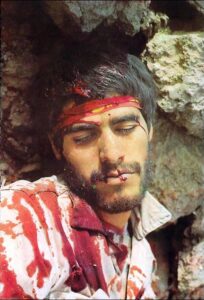

The war was driven by a huge dose of Shia imagery and sensibility feeding on the already established mythology of martyrdom of Imam Hussein in the Iranian culture. Some of the photographs in the earlier editions of the original five Sacred Defense books produced under Samadian’s supervision, are extremely graphic. “[T]he photobook, even more than the single photograph, is essentially about a point of view,” write Gerry Badger and Martin Parr in their Photobook: A History. The War Propaganda Council’s volumes were useful in fanning an Iranian sense of injury and mobilizing new recruits. The cover of the first book, a photograph by Kazem Akhavan, a young man who learned photography at the front, shows a close-up of a dead man’s head, wearing a checkered black and white headscarf, in a pool of blood not fully congealed on the ground where he has fallen. The ashen face of the dead soldier is only partially visible, and the viewer’s eye is drawn to the glistening red stain, fixed in its wet freshness. The second book includes a full-page color portrait of a chemically wounded soldier, whose raw face is covered in white cream. Another contains a section on children, labeling them the future warriors of Iran.

The state relied heavily on the chest-beating cult of martyrdom to depict Iran as a victim and not an aggressor. “Martyrdom is meaningless without memorialization and memorialization is not possible without a photograph,” writes Varzi. One of the most emblematic photographs of the war, taken by Ehsan Rajabi in 1986 on Iraqi soil east of Basra, six years into the war, depicts a soldier moments after his death. The blood trickling down his forehead matches his red martyrdom bandana so perfectly it looks as if it is part of the cloth. He looks like he is sleeping peacefully. The photograph could have been a fine example of Victorian memento mori had it not been for the dust on the young man’s face and his blood-soaked shirt. His posture, as he leans against a rock with his head bent slightly to his right shoulder, is saintly if not Christ-like. Photographs like this, vividly depicting death, are typical of Iran’s Shia-driven aesthetic of memorialization: The soldier finds virtuousness in death, following the glorious path of martyrdom. And in this photograph, he is beatified, frozen in his youth and sacrificed for eternity.

In contrast, Kaveh Golestan’s photograph of a dead boy, his chin shadowed by the first signs of stubble, is taken from a kneeling position. It refuses to make an icon of the boy or venerate his death. This is a corpse of a child, lying next to the feet of another dead soldier. His thumb held between his forefinger and middle finger looks alive and tactile. His face, with its mouth set in a bitter grimace and his eyes half open, is a death mask. The picture of Khomeini in his pocket raises the question: Was he wearing it like an amulet when he was killed, or was he adorned with it like a prize afterward? One way or another, the portrait links him in death with the leader of the Revolution.

The boy’s combat shirt has fallen open to his side and we can see the geometric pattern of his underpants. Maybe his mother sewed them for him, as mothers did in poor, traditional households—the domestic intrudes jarringly into the horror of war. The way he is placed in the middle of rubble and plastic sacks has nothing in common with the angelic death of Rajabi’s soldier; the photo by Golestan, who was working for America’s Time and Life, does not make death beautiful.

By the war’s end, the War Propaganda Council had produced additional books in the Imposed War series on all aspects of the conflict, from the battlefront to the home front, that include images taken by photographers with a broad range of professional affiliations. The books are uniform in style, with unsophisticated design and high-quality glossy pages and cover sheets, but the first book, described by Samadian as a catalogue of Iran’s grievances against Iraq for posterity, differs from the following ones. It is not numbered, as Samadian hadn’t anticipated further volumes. More significantly, in the first book, the introductory text is in Arabic, the language of the enemy, and English, the language of the international community, rather than Persian. The following books include Persian text as well and are organized around themes like the bombing of the cities or the volunteer soldiers. Lacking price markings, the books clearly were not intended to be sold on the Iranian market, but were produced in runs of 2,000 to 5,000 copies as gifts for foreign and domestic dignitaries. Samadian recalls Mir Hossein Mousavi, the prime minister during the war who green-lighted the project, saying he felt these books were his greatest cultural achievement in office.

❧

Saeid Janbozorgi, a volunteer soldier at age 15, discovered photography at the front. He was one of the photographers who documented the Iraqi chemical attack on the Kurdish village of Halabja in 1988 that killed some 3,500 to 5,000 Kurds and injured as many as 10,000 more (including Janbozorgi himself, who died in 2002 of chemical wounds he sustained while covering the massacre). At the end of the war Janbozorgi went to university to earn a degree in photography. His thesis, subsequently published as Photography in War, looks at the global history of war photography and connects the genre to its emergence in Iran. In it, Janbozorgi lists 39 Iranian photobooks devoted to various aspects of the war and 218 Iranian war photographers.

Janbozorgi describes war photography as an art, and at the end of his thesis, completed in 1997, he recommends that Iran make a concerted effort to collect and preserve the scattered photographs of the war with Iraq. In 2001, eight of his colleagues who had covered the front followed Janbozorgi’s advice and, with him, founded the Sacred Defense and Revolution Photographers’ Association. They published Janbozorgi’s thesis, which serves as an informal manifesto for their work.

Housed on two floors in a drab concrete building behind a traffic-filled boulevard in central Tehran, famous for its jewelry shops and, more recently, hip cafés frequented by young Tehranis, many born years after the war, the Association’s work marks a shift from the duty of documenting the war to the imperative to remember it—and in a particular way. Like veterans of wars the world over, Fereydouni and his colleagues have a special bond with the war and a special stake in its commemoration. The war photographers, who come in and out of the Association’s office in the afternoons to shoot the breeze with their old colleagues over glasses of sweet black tea and freshly baked bread and cheese, did not serve as disinterested journalists, but as committed members of the troops. Fereydouni has described his camera as his “dog tag.”

The Association’s first project was to extend the series of The Imposed War: Defense vs. Aggression photobooks of the 1980s, adding three new volumes. (The last is devoted to “Martyrs.”) Funded by the Basij Mostazafin, a paramilitary group founded in the early days of the Revolution and incorporated into the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the Association has been able to produce expensive photobooks—17 in total, so far—and sell them at affordable prices. Some of the books focus on various provinces and their roles in support of the war, and some are monographs dedicated to the work of individual photographers. Serving the sacred war was enough for the photographers at the time; they didn’t care about credit or copyright. In the war’s aftermath and the effort to safeguard its memory, they no longer wish to be anonymous. The monographs acknowledge the person behind the viewfinder.

“They don’t seem to have edited very effectively,” observes Magnum photographer Gilles Peress, whose own Telex Iran, published in 1984, is one of the most celebrated photobooks on the Iranian Revolution by a foreign reporter. Its fragments of the staccato telexes he sent out to his editors in place of captions perfectly capture the urgent nature of the events on the ground. Rather than carefully selecting images according to principles of composition, light, clarity, and focused storytelling, the editors at the Association sought to honor photographers for their service and to highlight the wide spectrum of images they captured as they had the front almost all to themselves. They snapped everything: the wounded, the dead, the weary, the bored, the eating, the standing around, the sleeping cuddled together in a grave for warmth and safety. Aesthetic quality was not the point. Still, the Association works meticulously to verify the time and place of every photograph.

Some soldier-photographers, like Fereydouni, became highly accomplished. His best-known image, reprinted by the Association both in its “Martyrs” volume and as the cover of Fereydouni’s monograph, is regarded as a “masterpiece” by Abbas Kowsari, one of Iran’s top photojournalists today. The photo depicts a soldier at the moment of his death. His head is wrapped in a makeshift cloth to stop his bleeding, the white of the cloth framing his face and echoing the white of his eyes as they roll into his skull. It seems he is looking up to something higher. He is held by an older soldier, who wears a helmet with the words “Ya Seyed-al-Shohada” (Hail Lord of Martyrs, referring to Imam Hussein). A motorbike lying on the ground behind the soldier suggests that he is part of the unit known as the “angels,” who outran the enemy on their fast vehicles, supplying their colleagues with support and sabotaging the enemy on the battlefield. He, too, is looking up at something way above him as he crouches next to the dying boy. The viewer follows the line of his eyes and of the boy’s death stare, and the image offers a metaphor of transcendence: The martyr, leaving behind a trench strewn with the detritus of war and surrounded by sandbags, ascends to heaven.

One might expect that the war loyalists would welcome commemoration of the war by younger photographers, who were children during those harrowing eight years, but Association members sometimes question the motives of a new generation of photographers, who are conversant in the trends in conceptual photography and have breached the sacred cordon around the war, scaling it down from epic proportions. Most of these photographers were at some point students of Bahman Jalali, who taught social documentary photography at various universities for 30 years before his death from cancer in 2002.

Among them, two women, Shadi Ghadirian and Gohar Dashti, have counterintuitively introduced the domestic element of life during the conflict in photo projects made two decades after the war’s end. Ghadirian’s series Nil Nil (2008) embeds a soldier’s paraphernalia into the private space of a home. A hand grenade sits among the fruit in a crystal bowl; a pair of combat boots rests next to a pair of red stilettos while a helmet hangs from the clothes rack. Ghadirian was 14 when the war began. “The war was a big deal in my life,” she says. “It was far, but it was scary. Even more when it came to the cities and affected us physically.” She once asked her mother why she let her and her siblings go out during the last two years of the war, when Tehran was hit by a missile a day. Her mother answered, “We had to live our lives.”

Members of the generation born in the 1970s and 1980s share a bond of war memories. They heard about it at school, watched it on TV, and, more devastatingly, felt it through the fear of their parents during urban bombardments. On Iranian social media, they sometimes post, in a nostalgic way, the sound of the bombing siren. Orkideh Behrouzan, a medical anthropologist, writes in her Prozak Diaries that “the self-identified ‘1980s generation’ in particular, repeatedly returns in its artistic and cultural expressions to the war’s sensory prompts in order to claim their cultural aesthetics, identity politics, and generational sensibilities.” Dashti, born the year the war started, is from Ahwaz, a southern city near the war zone. She remembers the sirens that warned of incoming enemy jets. “My brothers and I used to race to the roof of our house to collect the spent ammunition, which was still hot,” she says. “There was a competition with the kids in the neighborhood to see whose house got more.”

Her series Today’s Life and War (2008) stages the everyday life of a young Iranian couple in the middle of a battlefield, meshing the war front with the home front. She shot the series in Cinema City, an outdoor studio just outside Tehran, dedicated to the making of war films. After her photographs came out, the authorities in charge of the space, displeased by her version of the war, decided not to allow anyone else to use it for independent work.

These photographers are claiming their share of the memory of war by relocating its trauma into their own experiences and working the narrative away from the official version. By placing the war in a domestic context that is modern and middle-class, they are basically saying, “We were all affected by this.” The man and woman in Dashti’s photographs differ visually from the stereotype of the typical war family promoted by the state: the lower economic strata of society depicted as the pious and the pure who responded to the call of the Imam of the Age, Iran’s messiah, to save the country and the faith. Dashti’s family comprises a modern, urban couple. The young woman is not wearing a chador. She has a mobile and a laptop, bringing the legacy of the war forward in time, commenting on its continuing and pervasive reach.

While projects like Dashti’s and Ghadirian’s were breaking taboos in the representation and memory of the war, Maryam Zandi began to sift through the negatives of the photos she had taken during the Ashura march and the days following it back in 1978, which she had moved from house to house for 36 years, for fear of their being confiscated or damaged. She first sought a permit to publish her photographs in 2008, during the presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad; the censors insisted that 30 photographs be taken out of the collection. Zandi and her publisher, Mahmoud Bahmanpour of Nazar Publications, held back. When Hassan Rouhani became president in 2013, promising a more open cultural atmosphere, Zandi wrote to his office demanding to know why her book was deemed problematic (and also questioning why she had been vetoed to head the new photographic association she had helped found). It took the Rouhani government eight months to grant her the permit to go to print; there were no instructions to delete any of her photographs. In 2014, Nazar published Zandi’s monograph, Enghelab e 57 (The Revolution of ’79).

The book uses facsimiles of old newspaper pages from crucial days of the Revolution both for its dust cover and to provide context within. Bold Persian typeface on the front page spells out a quote by Ayatollah Khomeini: “There is no dictatorship in Islamic governance”—a sentiment that can be read ironically or literally depending on how one views Iran’s trajectory over the past four decades.

The first run of 2,000 copies sold out and the book went to a second printing. Zandi ascribes its success to two factors: “It was published independently from the government and it showed the events without an agenda,” she says, adding an explanation for its appeal to different demographics. “For my own generation, it’s like revisiting their memories; for the younger generation, it was seeing things that they had not seen before.”

Bahmanpour elaborates: “The further we get from events, the more interesting they become for the reader. Qajar Iran [the 1785–1925 period of the Qajar monarchs’ rule] is like 1,001 Nights for Iranians now. The Revolution is similar because it’s a mysterious time for the youth, who are fascinated by the way people looked and dressed.” The population of Iran has more than doubled since the Revolution and the younger generation is curious about the Shah’s time, which they imagine as a paradise of social freedoms. The photographs they have seen typically portray the Revolution as conducted solely by the Islamists. In Zandi’s book, she and Bahmanpour gave a double-page to a photo of a young woman with a mass of fuzzy hair, punching her fist into the air.

To the extent that there have been some openings for multiplicity in remembering key events of the Revolution and the war, Bahmanpour credits a kind of ignorance. The regime’s attitude hasn’t really changed, he suggests, but the censors have. “They are young and they don’t know the visual codes of the time,” he says; they simply follow a given set of guidelines.

When, just last year, Nazar published The Revolutionaries, a book of photos by Kaveh Kazemi, another independent photographer who was inspired by the success of Zandi’s book, the censors objected to images of demonstrations against the hejab in 1978. They didn’t want pictures of war dead. “But then,” Bahmanpour remarks, “they didn’t notice that the MEK [arch-enemies of the regime] were shown in four different photos.” Kazemi’s most famous photograph, which shows a soldier sobbing next to the body of his dead brother, was widely circulated abroad during the war and was admired by the regime’s first prime minister, but censored by the second, who feared it would weaken war morale. It now occupies a double-page spread in The Revolutionaries.

Embed from Getty ImagesThe Sacred Defense and Revolution Photographers’ Association—which also has to submit its work to the censors—is capable of thwarting projects that don’t serve the valorous version of history that they devote themselves to. Bahmanpour recalls how the Association would not cooperate in publishing a book about the war with Ghadirian as editor, because she had not preceded the word “war” in her title and elsewhere in the book with the word “imposed.” Despite their semantic zeal, Bahmanpour sees some fundamental changes taking place in their attitudes: “The guys who photographed the war have lost their ideology and don’t want to be identified as revolutionary. They feel they were tricked, that they were not appreciated,” he says. Indeed, Fereydouni expresses some bitterness over that lack of appreciation. “From the leader to the ministers, they always say they owe everything to the war, to the martyrs and the POWs—this is the regime’s main slogan,” he says. “But factional politics takes over.”

In 2016, the Association took the big step of publishing a book by a foreign photographer, Michel Setboun, notwithstanding the highly critical remarks in the book he published in France decades earlier. The Association owns a copy of that book and the means to have translated it—one of their young researchers is the translator of Susan Sontag’s On Photography into Persian. Instead, they went through Setboun’s extensive archive to produce a book almost three times bigger than his original, with an elegiac Persian text. The result, Times of Revolution, is a generous, 330-page volume, which includes Setboun’s image of people standing on the unfinished building waiting for the big march to begin. Setboun visited Iran for the book launch in 2016 and to meet the Association’s photographers.

That same year, a game designer in Brooklyn, Navid Khonsari, was also using the French photographer’s work to create scenes of the Revolution for an interactive video game that takes the player through the Iranian uprising via the eyes of a fictional young photographer named Reza. Having worked on bestselling games like Grand Theft Auto, Khonsari, who moved to Canada with his family shortly after the Revolution, when he was ten, wanted to use the engrossing genre of the video game to engage players in documentary material. In the game he created, 1979 Revolution: Black Friday, when Reza snaps a good shot, the screen shows one of 70 images by Setboun. For instance, standing on a rooftop, Reza is asked to take photos of the demonstrations in the streets below. Each time the shutter clicks, a photo by Setboun pops onto the screen.

Khonsari’s choice of a photographer as the protagonist was not a whimsical one. The role of photographers as first-hand witnesses of events and of photographs as legitimate documents is crucial to the critical engagement he hopes to achieve for his players. “A photographer is one degree separated from the events taking place,” he said in a Skype interview. “It also gave us the chance to incorporate an in-reality aspect, so that if you take a photo as the main protagonist in the game, we can show the real one beside it.” From the outset, Khonsari intended to show an aspect of the Iranian Revolution outside the standard narrative: “That it was a people’s revolution, that it started off as peaceful, but fractured into the way that it did. Putting the player in the role of a photographer provided the narrative while the documentation aspect legitimized the authenticity of the story.” As Reza encounters people from different factions, he faces a series of choices—for instance, whether to accept from an Islamist friend a cassette tape of the Ayatollah’s rousing speeches—and the option the player selects sets the course of the action at each juncture, until Reza is imprisoned and interrogated and the decisions he makes could prove fatal. “My part is taking pictures, not choosing sides,” Reza tells an activist friend.

Soon after the game’s release in 2016, Iran’s National Foundation for Computer Games banned it as ”anti-Iranian,” and warned Iranian families that “games like this can poison the minds of the youth about their country by means of false and distorted information, and also damage their spirits” according to the Tehran Times, Iran’s official English-language daily. For four decades, the state had propagated a singular narrative of the events that led to the establishment of the Islamic Republic. Here was a game, with a wider reach than conventional media, especially among the younger generation, that dared tell the story of the Revolution from a different point of view.

The contradictory uses of Setboun’s images—in the Association’s book and in Khonsari’s game—reveal a different kind of danger: that of the nature of photographs and their fluid fidelity to the truth. As Sontag writes in Regarding the Pain of Others, “The photographer’s intentions do not determine the meaning of the photograph, which will have its own career, blown by the whims and loyalties of the diverse communities that have use for it.” What looks like the valorization of martyrdom in one decade can turn and become a testament to horror, stirring antiwar sentiments in place of military and national pride. Setboun’s photographs have ended up in the middle of the rope of memory, tugged from two sides that each wish to tell their own version of history.

It would be an exaggeration to say that, today, history is up for grabs, but the wrangling over it is more visible than ever before. No one would have predicted ten years ago, for instance, that Fereydouni and his colleagues would consider displaying their photographs in a joint exhibition in one of Tehran’s swankiest new shopping malls or that they would have made a stir with an exhibition last year at Tehran’s Artists Forum called One Roll of War, which featured a spool of photographer Hamidreza Vali’s film that had remained undeveloped since the war. For the veterans of the Association, the exhibition presented a slice of heretofore unseen life during wartime, while young viewers saw a commentary implied by the evidence of decay and discoloration that age had inflicted on the negatives. No one could have guessed that the old photobooks from the war years would be sought after at shops like Dehkordi’s as commodity artifacts rather than as tributes to the Sacred Defense.

Even as anyone who wants to take on the photographer’s role in playing Khonsari’s 1979 Revolution: Black Friday inside Iran can manage to find a way around the ban, the regime continues to festoon the cities and towns of Iran every August on the anniversary of the liberation of Khorramshahr with posters and banners bearing a photograph by Mohammad Farnoud. This iconic war image, which has also been painted as a mural on the walls of Iranian cities, shows a group of young men, one with the barest trace of a mustache, running with their weapons held against their chests, their heads turned slightly to their right. They are wearing bright red bandanas on their foreheads with the words “No god but Allah” in Persian calligraphy. The annual proliferation of this image is accompanied by the slogan “What if we hadn’t resisted?”—a gesture meant to ensure that there is no question in the minds of today’s citizens that the war was necessary for the survival of the entire country, not just the regime.

As a new generation born after the war comes of age and will boldly take to the streets against the regime—thousands protested in January against high unemployment and inflation—the Iranian state works to shore up its power, in part by trying to mold its citizens’ memories of the Revolution and the war. According to political scientist Farideh Farhi, attenuating memories of the war pose a problem for the regime. “Fundamental fissures seem to rend Iranian society,” writes Farhi, “a society in which at least part of the population, voluntarily or involuntarily, went through a very intense experience of war. Yet it also contains a much larger segment of the population that, for good reason or bad, apparently wants to leave the war and the values propagated during the war period behind.”

❧

In a scenic spot between downtown Tehran, fashionable during the Shah’s time, and the newly favored north of the city, where opulent tower blocks dot the slopes of the Alborz Mountains, sits a new museum dedicated to the memory of Iran’s Revolution and its eight-year war with Iraq: the Museum of Sacred Defense, which opened in 2012. It sprawls across 50 acres of prime real estate that includes its own hills and valley, neither visible from the nearest motorway nor easily accessible.

Unlike the old Museum of Martyrs downtown—a collection of dusty displays of personal artifacts belonging to the war dead—the new museum is equipped with the latest in digital technology, recreating history in a series of installations that rely heavily on photographs. Seven distinct halls are inspired by Attar’s “Conference of Birds,” the 12th-century poem about the seven stages of spiritual development called for in the quest for truth. Each hall is dedicated to a different stage of the Islamic Republic’s early history, from the success of the Revolution through the war years. In the first hall, giant photographs of Ayatollah Khomeini rotate in a slideshow projected on a huge slatted wall. On the opposite side of the room, small TV screens repeat, in an endless loop, the moment a tearful Shah left the country.

The museum’s extensive gardens and waterfall are used for special occasions marking various war-related or religious dates. Children and families can picnic among numerous tanks, two jet planes, and six rockets, not forgetting the blown-up remains of cars belonging to Iran’s assassinated nuclear scientists.

On a midweek day in January, the museum is empty of visitors. Six guides—the women in black chadors, the men smartly dressed in suits—sit behind a desk waiting for someone who might want to be shown around the giant memorial site. Men in overalls wander around the seven halls cleaning the installations. Asked about when the museum is at its busiest, one of the janitors says, “Groups come sometimes, a hundred people or so.” He pauses. “But honestly, ordinary people, they don’t want to be reminded of the war.”

Haleh Anvari is an artist and the founder of AKSbazi.com, a crowdsourcing site about Iran.