An important process in Persian cooking involves simmering. It helps thicken the brew and bring oil up to the surface.

In the old days, cooking oil was an expensive and sought-after commodity. Thus many Persian phrases referring to “grease” or “oil” imply money or luxury.

Sibilesho charb kon, for example, “grease his mustache,” means give the guy a bribe. A slick oily beard after a meal implied the consumption of a rich oily meal, the province of a certain elite.

Noonish to roghaneh: “his bread is dipped in oil”—he’s raking in the dough.

And so, Yek ashi barat mipazam keh yek vajab roghan dashteh basheh. Literally, “I’ll serve you up a pot of ash with a nice fat coating of oil.”

A form of doubletalk and sarcasm, this is actually a threat. Not only are you not going to get that delicious ash—a popular Persian stew made with greens, beans, and noodles—you’re going to get poisoned. Revenge is in store.

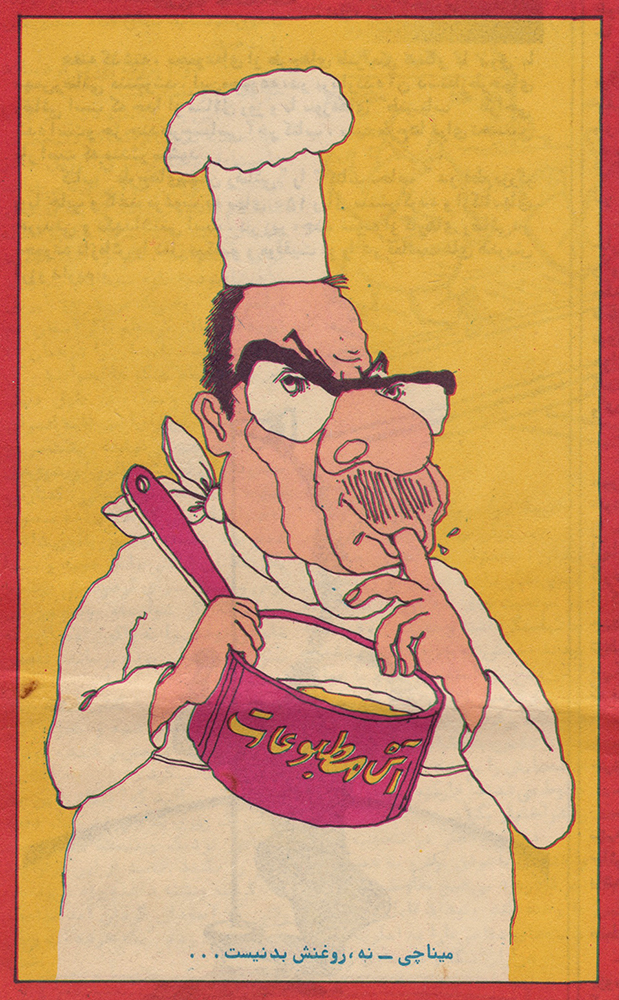

In this cartoon, published by Ahangar newspaper on August 7, 1979 (16 Morad 1358), Nasser Minachi, the first head of Ershad, the precursor to the Ministry of Islamic Guidance and Culture, is depicted as a chef with that pot of promised ash. In shorthand here, “Press Stew.” Under the ministry’s jurisdiction, media suppression and censorship run rampant to this day.

Minachi believed Islam should be modernized. Like his friend the late Ali Shariati, an ideologue who fired up the Islamic left in the 1970s, he was considered a reformist. Like other early reformists of the Islamic Republic, he became a victim of the political regime he helped establish.

After the takeover of the US Embassy in November 1979, Minachi was accused of being an American agent and temporarily arrested. Upon his release, he was booted from his job and prohibited from leaving the country.

Even after his death, he was not spared. In his will, he had asked to be interred at the Hosseinieh Ershad, an iconic progressive religious organization that was his legacy.

He was buried in Qom instead.