The French-Iranian Film Connection ❺

Cinema existed long before articulate speech appeared. Image, still or animated, goes back to the very beginnings of mankind. It preceded every other means of communication. . . . [R]eflect for a moment on prehistoric cave drawings and especially on what we know of the phenomena of nocturnal dreams and waking fantasies.

The source of this expansive view of the cinematic, Fereydoun Hoveyda, led a professional life that may seem like a waking fantasy. The younger brother of Amir Abbas Hoveyda, Iran’s prime minister between 1965 and 1977, Fereydoun was, among other things, a literary novelist, a science-fiction writer, a film critic, a social analyst, a screenwriter, a visual artist, co-drafter of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and ambassador to the United Nations. Born in 1924 in Damascus, where his father headed the Iranian consulate, and subsequently raised in Beirut, he would become “open to the universe,” as he put it, with friends ranging from author Sadegh Hedayat to philosopher Raymond Aron to stage director Robert Wilson to everyone’s friend, Andy Warhol.

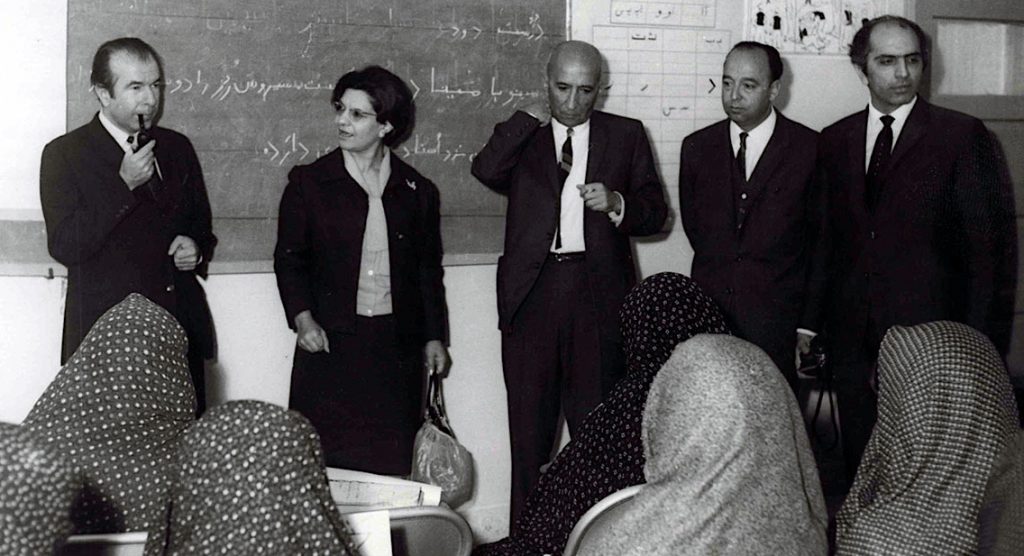

Having received his education at French schools in both Syria and Lebanon, Hoveyda joined the Iranian foreign ministry and, in 1946, was assigned to the Paris embassy. There, two years later, he met the Shah and completed his doctorate in international law and economics at the Sorbonne. In 1952 he left the diplomatic corps but stayed in Paris to work for UNESCO’s Department of Mass Communications, where he would spend nearly a decade and a half facilitating freedom of the press and media modernization in the developing world. It was during this period that Fereydoun Hoveyda became a core figure in the French-Iranian Film Connection.

Hoveyda was film-crazy and Paris in those years was a cinephile’s paradise. “Throughout the fifties, I went to the cinema almost every evening,” he later said. In 1953, at the 60-seat Cinémathèque Française, he befriended the famed film theorist André Bazin, editor and, two years prior, cofounder of Cahiers du Cinéma, along with a protégé of his, 21-year-old François Truffaut. Hoveyda joined the influential journal’s editorial board and, in the August–September 1955 issue, published what would be the first of his many critiques in it—a review of the Warner Bros. creature feature Them, in which he praised its explicit grappling with atomic-age dread: “Today, as the ‘big’ films have in large part become occasions for ‘escapism,’ it’s precisely a genre intended as ‘escapism’ that drags the spectator back, a bit despite himself, to exhausting reality.”

Associating near daily, “afternoons and evenings,” with future Nouvelle Vague directors Truffaut, Jacques Rivette, Claude Chabrol, Éric Rohmer, and Jean-Luc Godard, over the rest of the decade Hoveyda was a frequent, witty contributor to the monthly Cahiers film diary, “Petit journal intime du Cinéma.” He wrote a multipart appraisal of the “Grandeur et décadence du Sérial” (“What has happened to the serial is what happens to all other cinematographic genres: as we have tried to impose strict rules on it, all poetry has disappeared, giving way to poor, dried-up skeletons comprising not even a shred of flesh”) and a lengthy essay on science fiction in the time of Sputnik; conducted an interview with acclaimed director Roberto Rossellini, with whom he had already collaborated on the script for India: Matri Bhumi (1959); and took on the daunting task of reviewing The 400 Blows (Les quatre cents coups, 1959), the feature film debut of his closest friend at the journal (“Les 400 Coups is not a masterpiece. So much the better for François Truffaut!”).

For a time, Hoveyda also reviewed a couple films a month for the science fiction magazine Fiction and contributed as well to Positif, Cahiers’ main competitor, both under the pen name F. Hoda. (He was actually published in Positif even before its rival: an essay on “Horror and Science Fiction” in November–December 1954.) He turned increasingly to novel writing in the 1960s, while continuing to write regularly for Cahiers. At the turn of the decade, he produced two of the most important film essays ever, at a rank just below the 1954–57 pieces in Cahiers and the weekly Arts in which Truffaut denounced the middlebrow “tradition of quality” in French film, proclaimed the politique des auteurs—the “policy” that the director of a film could be, should be, is, no less an author than is the writer of a book—and called on young filmmakers to make the “film of tomorrow”: “even more personal than a novel,” an “exalted adventure,” “an act of love.”

With “La réponse de Nicholas Ray” in May 1960, Hoveyda took a failed Hollywood studio film directed by a Cahiers favorite, declared it “admirable” and implicitly “perfect,” and proceeded to illustrate how, despite its shopworn script (“Party Girl’s story is idiotic. And so?”), Ray’s mise-en-scène (more or less, his formal treatment of the narrative substance) had made something out of nothing: “inventions keep raining down” in “a cascade of ideas.” Hoveyda was both true and, to use the anachronistic term, trolling when he declared, “If one continues to find Party Girl idiotic, then I cry, ‘Long live the idiocy that so dazzles my eyes, fascinates my heart, and opens the kingdom of heaven to me.’” (Hoveyda’s argument is heavenly. Party Girl is . . . decent.) Over several years, Truffaut had issued a transformative polemic: Our heroes have control. Seize control. Hoveyda now offered a provocative paradigm: See? With just formal control, you can turn even muck into magic.

When you’ve properly provoked with specifics, you’re sure to be invited to write a grandly conceptual follow-up. In “Sunspots” (“Les taches du soleil”) of August 1960, Hoveyda first takes on the value of film criticism—cheekily eviscerating the daily and weekly kind that aims to “predetermine the viewer’s choice,” while defending Cahiers’ monthly sort that “engages in a dialogue” about works already seen. Then, invoking his Ray blast, he declares, “When I assert that everything is expressed on the screen through the mise-en-scène, I in no way contest the existence and importance of the subject matter.” He proceeds: “I simply want to call to mind that the property of a great auteur is precisely knowing how to metamorphose through his technique the most idiotic plot.” The sentence’s modest preamble barely disguises that “the property” makes a claim even more radical than his previous one.

Hoveyda’s other major pieces in the 1960s included two more interviews with Rossellini and the first extensive consideration of the new cinéma verité movement. Among his reviews, one of the most pointed came under his sometime Cahiers pen name, Fred Carson—a drubbing of the big-budget, bien-pensant anti–atomic bomb drama On the Beach and its baldly stereotypical characters: “One swiftly begins to hope for their annihilation. Alas! It’s a very long wait.”

Hoveyda, by this point, was more willing than any of his Cahiers comrades to fully commit to a taste for pop cinema: not only did he cite Party Girl as one of the three best films of 1960, he gave sole pride of place to Mario Bava’s goth-horror Black Sunday in 1961 and sat not one but two Jerry Lewis films atop his 1963 ten best list. Of the 27 other critics who ranked their Cahiers lists, just three had The Nutty Professor in their top three; among the total of 41, just one other named The Errand Boy at all. Yes, French aesthetes’ fabled love for the man they dubbed the King of Crazy leans in part on an Iranian’s self-assurance. His last signed item for Cahiers during the era appeared in August–September 1964, a review of director John Huston’s Freud, the Secret Passion: “[The hero], denied all possibility of poetry, is suddenly revealed as a poet. This last aspect of the film undoubtedly explains the resistance of many spectators and critics. In this era of numbness, one doesn’t like to have one’s inner comfort disturbed.”

In 1966, with his brother having recently assumed the premiership, Hoveyda left France for Iran; he rejoined the foreign ministry, serving as an undersecretary. He was appointed UN ambassador in 1971, a position he held until the end of Pahlavi rule. In his 1980 account The Fall of the Shah (La chute du Shah)—first published in Paris, like a dozen other of his books—Hoveyda excoriated the corruption of the monarch and his kin, stating further that “the example of the royal family was a source of contamination which infected every level of society.” Few would contest the breadth of that “contamination,” though the story in Hamid Naficy’s magisterial Social History of Iranian Cinema that Hoveyda himself once summoned agents of SAVAK, the Shah’s notorious security service, to haul away a filmmaker over a political spat is thinly attributed and deviates widely at least once from verifiable fact.

Following the Revolution, and the grisly execution of his brother after a sham trial, Hoveyda settled in the United States. Though he focused mainly on international affairs as an author and policy consultant, six years before his death in 2006, he produced his lone book to focus on film: The Hidden Meaning of Mass Communications: Cinema, Books, and Television in the Age of Computers. While he laments how many of his Cahiers colleagues who became filmmakers lost their artistic edge over time (or in the case of Godard, “turned to ‘political’ cinema devoid of any artistic value whatsoever”) and how contemporary directors are becoming “mere technicians,” he concludes with a startlingly optimistic vision of the next “film of tomorrow,” even as he exemplifies the humility of an intellectual ever mindful of what tools he is working with:

I remember what the great film director Luis Buñuel once told our group of “cultists” and “film fans” at Cahiers du Cinéma, Positif, and other magazines in the 1950s during a visit to Paris. He said that we will reach the peak of filmmaking when we will be able to sit in a room, switch off the lights and project on a wall, directly from our brains and through our eyes, the stories that we conceive in our heads!

I am sure that, one day, technology will develop the revolutionary means to accomplish such a feat. Then film would become completely personal and reach the “essence” of auteurism. Then, everyone would be an auteur in the sense of the reviews my friends and I were writing in the ’50s and ’60s.

Then image would finally supersede word.

Or would it?

For the rest of The French-Iranian Film Connection, click here: [1] [2] [3] [4] 5