The French-Iranian Film Connection ❷

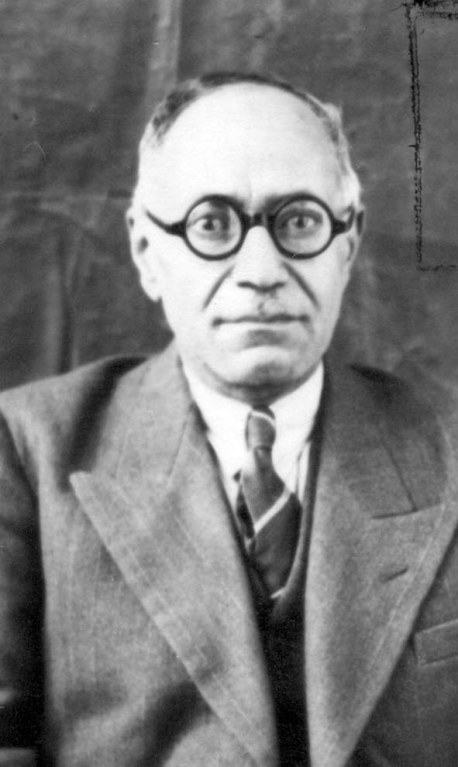

The first Iranian to set out to make a career as a filmmaker, Khan-baba Khan Motazedi, learned the craft during his years as a student in Paris. Motazedi was born in 1892 in Tabriz, where at the turn of the century the French Catholic mission established the country’s first public cinema. After receiving his secondary education at an Alliance Française school, in 1908 Motazedi left for Switzerland and ultimately France to study electrical engineering. In Paris, he took a job with the Gaumont Film Company, one of the world’s first motion picture studios, attaining the rank of cinematographer. When he returned to his homeland it was as a trained filmmaker, with a full complement of Gaumont equipment: camera, film stock, processing chemicals, and projector.

Back in Iran, Motazedi started his independent cinematic career by taking images of the everyday lives of his own family members—home movies, developed in the lab he set up in his basement—but soon began to accept commissions from the royal court, the military, and the education ministry, along with private businesses. The French-Iranian Film Connection had yielded Iran’s first full-time documentarian.

Motazedi shot innumerable newsreels and nonfiction shorts, some of great historical consequence such as one showing the Majles assembly in December 1925 as it named War Minister Reza Khan—adopting the new surname Pahlavi—as successor to the Qajar dynasty officially deposed two months earlier. The following April, Motazedi filmed his coronation as the first Pahlavi king, Reza Shah. Among Motazedi’s other subjects were Crown Prince Mohammad Hassan Mirza, brother of the last Qajar monarch; the groundbreaking for the National Bank of Iran in 1928; military parades and horse races; and many films devoted to the country’s rapidly expanding network of railways, roads, and bridges. According to one source, he also made a comedic three-reeler (roughly half an hour) that would have been among the first fiction films produced in Iran, though evidence for its existence is scant.

In the late 1920s, Motazedi established several movie theaters as the import of overseas films rose in concert with Reza Shah’s modernization campaign. In 1928, a year that saw 305 films from abroad make their way to Iran, Motazedi opened the San’ati Cinema, the country’s third devoted to female audiences. Like the previous two, it closed after only a few months, in this case the result of a massive fire—possibly set by an anti-cinema group especially aggrieved with female patronage of the new medium. Undeterred, he went on to found the Tammadon and Pari theaters, where, in each case, one side of the house was accessible to men and the other to women. Motazedi (along with another Paris-educated entrepreneur, Ali Vakili) is credited as the first to make foreign films more intelligible to local viewers with the addition of Persian intertitles. Still-widespread illiteracy, however, prompted him to hire performers to read out the captions, in the manner of Japanese cinemas of the era.

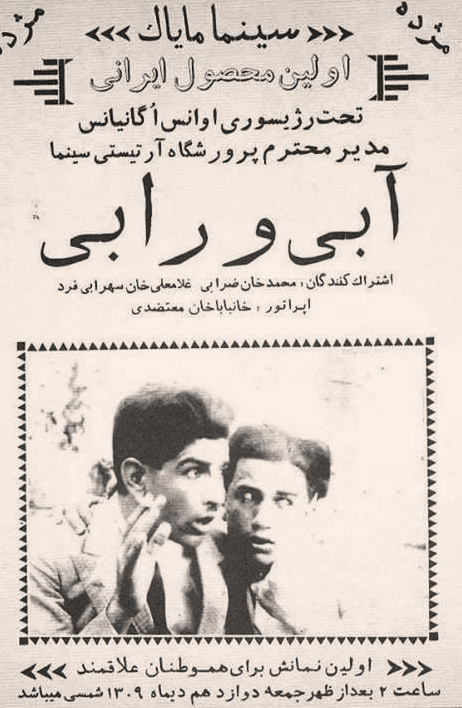

During this period, Motazedi began an association with a filmmaker of Armenian heritage, Ovanes Ohanian. Born in the Ashkhabad area, not long after it was ceded by the Qajars to the Russian Empire, Ohanian had studied at Moscow’s Cinema Academy. He arrived in Tehran in 1925 with plans to establish a small film school that would be the country’s first. By the end of the decade, cinema was burgeoning in popularity: in 1929, no less than 460 foreign films were imported to Iran. The following year, Ohanian wrote and directed what is recognized as the first Iranian feature film—Abi and Rabi (Abi va Rabi)—for which Motazedi, who was in a position to provide crucial financial backing, served as cinematographer. Abi and Rabi premiered on January 2, 1931, at Tehran’s Cinema Mayak, reportedly attracting many notables. (Some sources date the production and release a year earlier, respectively, seemingly due to confusion in translating from the Persian to the Western calendar.)

The film largely took the shape of a series of vaudeville-style sketches patterned on the antics of the internationally popular Danish comedy duo billed as Fyrtårnet and Bivognen (Lighthouse and Sidecar; known in Iran by their German names, Pat and Patachon). As with many now unavailable films from the silent era, it is not easy to determine how long this “feature” ran: One reference work puts it at an even 60 minutes. Online resources echo the claim that it was 1,400 meters long—77 minutes, if shot at the era’s average of 16 frames per second, though films were often projected at faster speeds. Whatever its length, and however thin its narrative thread, it was apparently a popular success. Motion pictures were still treated as an ephemeral medium, however, and when a fire broke out in the Cinema Mayak a year or two later, the only known print of Abi and Rabi was destroyed.

For the rest of The French-Iranian Film Connection, click here: [1] 2 [3] [4] [5]