The absence of independent journalism in Iran cannot be blamed solely on censorship and a lack of freedom. The political affiliations of supposedly independent newspapers’ owners and executives result in their narratives adhering closely to those of the government.

More than ever before, the management and nature of journalism in Iran is used as leverage for political gain. Not that this hasn’t long been the case. Iranian newspapers have traditionally been mouthpieces for political parties and organizations to disseminate their political views and spin.

These political maneuverings existed even in the three short periods of relative freedom of speech and the press in Iran: the post–Constitutional Revolution period (1906–21); from Reza Shah’s exile in 1941 until the coup against Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953; and in the brief euphoria after the 1979 Revolution.

But from August 1997, with the election of President Mohammad Khatami, certain politicians began to push their opposing agendas through various newspapers, giving an appearance of diversity in a number of news publications dubbed “independent.”

This group of newspapers that call themselves independent or “nongovernmental” in fact belong to a political tendency called “reformist.” These papers are not independent, and neither are they necessarily nongovernmental. Their autonomy is compromised not only by the government subsidies they receive, but also by their close ties to major regime institutions.

For example, Mehdi Rahmanian, the managing director of Shargh newspaper, belongs to the reformist camp and served as city governor of Chabahar, in Sistan and Baluchestan province, during the Khatami period.

Elias Hazrati, the permit holder (grantee of the official license to publish) and managing director of Etemad, is a two-time reformist member of the Majles; he recently rose to the chairmanship of the Etemad Melli political party.

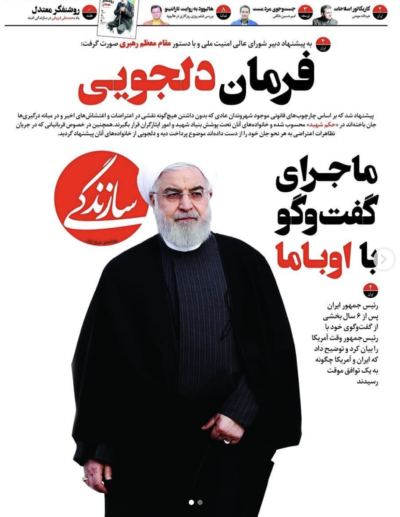

The Sazandegi newspaper is an official organ of the Kargozaran party, whose leaders are all former members of the Rafsanjani government. The director of the newspaper, Mohammad Qouchani, is a Kargozaran party member, a media adviser to the government, and was recently appointed as secretary of the Center for the Preservation and Publication of the Works of Hassan Rouhani.

The permit holders of lesser-known reformist newspapers such as Hamdeli and Arman Melli have similar backgrounds. The permit holder of Hamdeli, Valiollah Shojapourian, was a reformist MP, and Hossein Abdollahi, director of Arman Melli, was close to Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and was his adviser at Islamic Azad University.

These newspapers closely represent official factions of the Islamic Republic and not varying or opposing points of view.

Even though these newspapers cover important nonpolitical events like the passing of legendary maestro Mohammad-Reza Shajarian, regarded as a national treasure, they do so to appear as if they are reflecting the voice of the Iranian people. But the moment they sense the faintest opposition to the Islamic Republic, they either fail to cover those events that are close to the hearts and thoughts of the people, or they oppose them, as was the case with the mass demonstrations of December 2017 and November 2019.

Politically motivated journalism

A few characteristics:

“Tribal” Journalism

The first and most important characteristic of this type of reporting is its factional nature, meaning it represents the interests and goals of a particular political party with devoted coverage of their speeches, spin, and analyses.

They hire staff more on the basis of loyalty than professional or related experience.

For example, as the government changes hands from reformist to principlist (right-wing) and vice versa, the managers of Iran and Hamshahri newspapers change as well and groups of reformist or principlist journalists replace the old ones.

In 2017, when the reformists took control of Hamshahri, a reformist representative assumed the responsibility of reorganizing much of the masthead, and Javad Daliri, who had been editor-in-chief at Etemad, immediately took up the same position at Hamshahri. Mohammad Qouchani, the editor-in-chief of Sazandegi, has a regular team that manages and supports the magazine and newspaper groups under his charge.

This tribalism is also seen in the behavior of journalistic institutions such as the Association of Iranian Journalists (which is always controlled by reformists). In 2020, this institution delayed three months in showing any kind of reaction to the sexual harassment allegations raised by a number of women journalists, after which it announced the formation of a special committee to help those affected. But in practice, not only did they do nothing, but as a group of prominent independent journalists mentioned in a statement, they called the narrative of the affected women “immoral.” There are even reports that they reached out to the affected women in some cases in attempts to silence them so as to avoid any embarrassment for the press. By contrast, the truly independent journalists who work at these papers have no influence on the direction of the paper itself and remain sidelined.

The Lack of Training

Although the first generation of newspapers that were founded in 1991 (such as Hamshahri, Iran, and even Jame’h, one of the most professional postrevolutionary newspapers) didn’t treat the training of journalists as a matter of any importance, they employed trained and experienced journalists. Today’s generation of newspapers still places little to no value on education and training, meaning that not only do they suffer from technical problems in the writing and preparation of reports, but serious problems can be observed even in their Persian.

Government-Oriented Journalism

The third characteristic of this journalism, which is largely a corrupt result of the two characteristics discussed previously, is that a large share of all news items revolve around the speeches of various national personalities and officials, a tendency that has only intensified during the Rouhani presidency. Coverage of the remarks of officials is considered a news priority. For example, every word by the supreme leader and the president must feature on the front page. Some of these newspapers actually cover the remarks of the heads of other branches of government and ministers, whether they’re important or not. All of this has gone so far that the problems and demands of society are sometimes echoed by the same officials that are supposed to be responsible for answering them, making the whole issue of demanding accountability from government officials seem ridiculous.

These partisan and group affiliations and the looming threat of being shuttered heavily loom over the reporting of these so-called independent papers in a direction that, first, has importance for the reformists in the political arena, and second, supports the regime overall. For example, now that we are closing in on election season, the focus of the newspapers is on two issues: the elections and the JCPOA. Numerous editorials and reports are published daily on these two subjects. These two issues are covered in a way that represents the reformists’ official narrative and point of view and totally neglects the voice of the people. The elections are an important issue for the reformists, but not for a large portion of the population, which has lost hope in any change in the Islamic Republic’s behavior. In a poll by the Netherlands-based group GAMAAN, 76 percent of the respondents said they didn’t participate in elections. Even according to statistics from the Ministry of Interior, the turnout in the 2020 Majles elections was about 42 percent of eligible voters, and in Tehran the turnout was less than 25 percent. Some of the reasons for this abysmal level of participation are clear: the suppression of protests in 2017–18, the downing of Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752, the rising cost of living, the lack of hope for any change, the Iranian government’s mismanagement of the pandemic, and its reluctance to buy vaccines. All of this has not only increased people’s reluctance to participate in elections, it has also amplified opposition to the Islamic Republic.

While some Iranians support the return of Donald Trump to the US presidency since that would entail further pressure on the Islamic Republic, they are never covered in the press. As a result, it is unknown why this group of people supports increased pressure on the Islamic Republic in spite of the economic strain resulting from the sanctions, since addressing this issue would raise fundamental issues and call into question a US-engagement policy that is the pride and joy of reformists in the electoral arena. Be it due to censorship or self-censorship motivated by the desire to support the government and reforms (for which the JCPOA is a bargaining chip to use against rival groups), ignoring the question of why a certain sector of the population no longer supports or cares about the JCPOA shows that one cannot understand the reality of what is happening in Iranian society today through the reformist-aligned media.

The daily coverage of these newspapers gives the impression that everyone in Iran is anticipating huge changes after the elections. From the last week of February through early March, “elections” were covered every day in either news reports or interviews. On February 20, 2021, Shargh dedicated its front page image to Seyyed Mohammad Beheshti, with a headline—”If You Don’t Run for the Majles, the Doors Will Be Closed”—that quotes someone identified only as “the daughter of Maryam Behrouzi” (a former Majles member). A few days previously, on the night of February 17, an earthquake occurred in Sisakht and Shargh was unable to run any news about it due to the offices being closed for the weekend. And when their first post-earthquake issue was released on February 20, they thought it was appropriate to report on an earthquake that destroyed 3,000 homes on page 9, rather than on the front page.

The left and right corners of that February 20 front page bear election-related quotes from Seyyed Hassan Khomeini and Mohammad-Reza Aref, with the speeches from which they are drawn presented as news stories. On February 21, the same day that the shooting of people carrying fuel across the border in Saravan took place and turned into a week-long crisis in Sistan and Baluchistan province, the front page photos were dedicated to Abbas Abdi, Abdollah Ramezanzadeh, and Ahmad Zeidabadi, all reformist figures. On February 22, the front page was decorated with photos of Gholamreza Zarifian, another reformist figure; on February 23, there was a photo of Alireza Alavi Tabbar; on February 24, there was a photo of pro-reformist novelist Mahmoud Dowlatabadi, who did an interview with the editor, and the top headline concerned disputes in the Majles. On each day from February 27 through March 2, the photos of reformist heavyweights Ali Motahari, Hossein Marashi, Mohsen Armin, and Mahmoud Sadeghi, respectively, all featured on the front page alongside quotes about the elections, and the newspaper’s main headlines were about disagreements between the presidency and the Majles. There was another important development during the latter part of February and early March: the IRGC killings of ten or more independent fuel carriers and subsequent protests in Saravan. But Shargh didn’t run even a single story about the events.

Etemad newspaper has more diverse coverage than Shargh and its headlines consist of more than just news and quotes from the reformist political arena. More often than Shargh, it features images of non-reformists or urban spaces on its front page. Etemad had front-page articles on the Sisakht earthquake and the Saravan protests, with the report on Sisakht coming from the field. The paper’s main focus, though, just like Shargh’s, is the favored issues of the reformists, which currently include the elections and the JCPOA. These two issues have been followed in articles, analyses, and editorials in successive issues of the paper and on pages 1, 2, and 3.

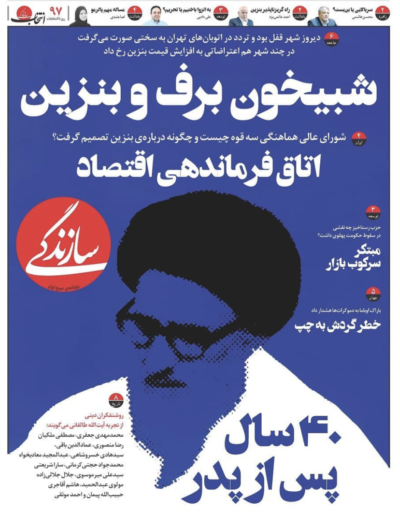

Sazandegi is even more transparent in showing its support for the current government than Etemad or Shargh. Apart from publishing quotes of members of the Executives of Construction party, it vigorously supports the Rouhani presidency. The news items appearing most prominently on its front page concern the elections and the Rouhani administration’s foreign policy. Sazandegi’s headlines smack of advertising and yellow journalism. For example, when the issue of human tests for the domestic Koviran vaccine was raised, Sazandegi covered it on December 30 with the extravagant headline “Beginning of the Downfall of Coronavirus.” Naturally, months after the tests concluded and the government had yet to announce a plan of universal vaccination, Sazandegi and the other reformist newspapers did no follow-up on the matter.

The photos on the front page of Sazandegi during the latter part of February and early March featured Kargozaran party members Hossein Marashi, Mohsen Hashemi, and Gholamhossein Karbaschi. From February 20 to February 28, the front-page photos featured: Joe Biden, Rafael Grossi, Ali Karimi, Ali Mottahari, Mohammed Bin Salman, Ali Karimi, an oil field, Donald Trump, Pope Francis, Ayatollah Sistani with the pope, and Ata’ollah Mohajerani. The top headlines were related to the photos, with some relating to the elections and others to government actions or interests in foreign policy, specifically the JCPOA negotiations. During these ten days, Sazandegi ran no report on the Sisakht earthquake or the events in Saravan. It appears that for the newspaper, these two events didn’t have the same value as Ata’ollah Mohajerani’s comments or Ali Karimi’s candidacy for president of the Football Federation. Featured items related to the Razzaq plan to issue licenses for limited fuel trade at the borders were almost literally old news—there was no new project to address the problem of fuel smuggling.

In each of the three aforementioned newspapers, the elections and the JCPOA are covered in the same way: election-related news about the rival faction and continuous, daily insider analysis. But in the case of events related to people’s daily lives, news coverage is often sporadic, without examination of the background or follow-up on any stories. The most important example of this is the coronavirus pandemic. For more than a year, COVID-19 has plagued Iran and the wider world, causing the deaths of over 75,000 Iranians to date. But it is only occasionally covered in Iran’s newspapers, with news about it often not appearing for an entire week or more. In addition, while prior to 2017 these newspapers frequently featured independent and academic analysis, in the past few years, the analysts featured in the newspapers have been limited to those who belong to their own inner circles.

Turning a Blind Eye

It is due not only to government censorship that the newspapers don’t cover popular protests, but also to the reformists’ interests as a group which require that such news not be covered. Ignoring the 2019 protests marked the beginning of serious public distrust of the reformist newspapers. The way the 2019 protests were covered can be considered a turning point in the history of Iranian journalism.

The 2019 protests started on November 15, after the announcement of the increase in gas prices. From that date, when internet service was cut in Iran—for five days in much of the country, for over a week in some of it—Etemad, Shargh, and Sazandegi did cover the protests, but how?

None of these newspapers produced any on-the-ground reporting on the protests. Sazandegi was satisfied with publishing the statements of officials and the analysis of political activists who shared their opinions on the roots of the protests. There was no reporting on the phenomenon unfolding on the streets, the number of people killed, or the cities where protests were taking place. Rather than cover such important events, on the second day of the protests, Sazandegi ran a cover story with a photo of Ayatollah Taleqani and the headline “40 Years After the Father”–his death. The paper’s top story reported heavy snowfall in Tehran, and only under that headline were protests in several cities mentioned. During a week of protests, Sazandegi published articles supporting the government’s decision to increase gas prices. The paper’s top headline on November 20 was “The Margins versus the Center,” a metaphor for “villages and smaller cities,” on the one hand, versus “Tehran and other major cities” on the other, signaling the paper’s dismissive stance toward the protests. A week later, Sazandegi adopted a clearer stance against the protests. On November 26 through 28, the paper ran the headline “Interior Minister’s Narrative of the Crisis,” reported on the “Demonstration Against Destruction” (a reference to the usual pro-government demonstrations following popular protests), and covered “Burned Banks” rather than killed protesters. The flattering headline “Decree of Consolation,” decorated with a large photo of the president, who is supposed to bring justice, contradicted the coverage of these events. From the second day of the protests, Etemad made its stance against the protests clear. In a report called “Who Are the Ones Burning Down the City?,” the paper criticized protesters for burning banks, libraries, and ambulance stations. The report, which appears to be from the field but is in fact not, doesn’t mention any protesters who lost their lives apart from one person whose death was also reported by state news agencies. In its other reports, which focus mainly on the prepared statements of officials, Etemad wrote about the right to protest and the place of protest in expressing objections. In its November 26 edition, the top story covered the pro-government demonstrations, with the headline “Security for All.”

Shargh covered the protests with an air of calm. Its first report on the protests ran on November 17, which referred only to people gathering and causing traffic jams, neglecting to mention the repression of the protests. On other days and similar to the other papers, it examined the government’s policy of increasing gas prices. But on November 19, at the height of the protests, Shargh dedicated its cover photo to an image of Hassan Rouhani and current chief justice Ebrahim Raisi with the headline “Affirmation of the Protest, Condemnation of the Unrest”; the accompanying story affirmed the government’s position that the protesters were responsible for riots. In the days following, Shargh remained silent on the protests apart from one short column titled “Hear the Voice of the Protests.”

Both during and after the protests, a study of these newspapers yields no information on the protests, the number of those killed, the extent of the damage and how it was caused, or even the claim that the government demanded money from the relatives of those killed to reclaim the bodies of their loved ones. The newspapers condescendingly referred to the protesters as “marginals” who were attacking the “main body” of Iranian society, breaking laws, setting fire to banks and ambulances, and generally showing that they were unschooled in the proper “culture of protest.” It was only after the internet was opened back up that mobile phone videos were published to social media and public could at least partially ascertain the truth of what happened in those days. The videos even appear to show that the looting of the banks and smashing of car windows and some residences was the work of government agents themselves.

Shortly afterward, in an interview with the Tasnim news agency, Mohammad Qouchani, editor in chief of Sazandegi, and Abbas Abdi, a journalist and columnist at Etemad and Shargh, supported the government’s crackdown on protests. It is acceptable for journalists to exercise their right to their own opinions on transpiring events, but is it acceptable for a newspaper, as a channel of mass communication, to turn a blind eye to events that, according to some IRGC officials, affected 29 provinces and more than 100 cities and, according to an Amnesty International report, left at least 23 children dead? Is it acceptable for a newspaper’s field reporting to focus instead on traffic jams and feature an interview with a commuter who is stuck in traffic and can’t find a way out due to the cutting of the internet? Is it acceptable for journalists to sit in their offices in north Tehran, call protesters “an attack on the middle by the margins,” and suggest to them that they need to learn how to protest properly?

Appropriation and Theft of Symbols and Concepts

These papers either self-censor and turn a blind eye to events of societal importance, especially widespread discontent and protests, or cover them through the lens of official statements. They deliberately attempt to steal and appropriate the slogans that have been used to elaborate protestors’ demands at various points and try to reframe them as part of the regime’s narrative. One example is the well-known slogan “Neither Gaza, nor Lebanon, I sacrifice my life for Iran,” which first appeared during protest marches on the annual Quds Day event in 2009 and was repeated in 2017, when even Ali Khamenei reacted to it. Sazandegi used the “I sacrifice my life for Iran” part of the slogan in a January 7, 2020, headline related to the funeral of Qasem Soleimani. In other words, the newspaper distorts a slogan in protest of the Islamic Republic’s regional, Shi’a-oriented policy and erases the first part of it to laud the very person who not only played a key role in carrying out those policies but in the words of former IRGC commander Aziz Ja’fari, played an active role in suppressing the student protests of the 1990s. It is said that Soleimani also used forces under his command, the Holy Shrine Defenders (as the IRGC forces in Syria are known), to suppress protests in 2019.

Another example of this appropriation can be found in the framing of reformist figures as protest symbols. In the 2021 edition of its annual Nowruz feature, Etemad published a headline and cover image featuring Seyyed Hassan Khomeini, the grandson of Ayatollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic, and called him “a hopeful protester,” which provoked numerous reactions on social media. The large picture and headline shows how the reformists are interested in casting their own favored figures as representatives of the people and replacing the desperate protesters whose protest will be met with bullets, a long prison sentence, or even death in prison. Bear in mind that Seyyed Hassan Khomeini receives an annual budget from the government to run organizations such as the Institute for the Compilation and Publication of Imam Khomeini’s Works and the Mausoleum of Ruhollah Khomeini. He manages the Jamaran news website and maintains good relations with various elements of the regime. Can he really be a representative of the people and a narrator of the oppression currently being visited on them, solely because he was once disqualified from an Assembly of Experts election?

These “independent” Iranian newspapers are neither independent, nor do they take a balanced look at political and societal events. Censorship, self-censorship, and one-sided, biased pro-reformist views on the issues are more reflective of their group interests and concerns than a reflection of what is actually happening in Iran.