What Revolution photos tell us and what they don’t

Forty-two years ago, when I was 11 years old, I bought my first book of photos from Payam bookstore near the entrance to Tehran University, a few months after the Revolution. The streets outside the university were lined with shops and stalls selling books, newspapers, and magazines, and full of energetic political debates among the passionate and hopeful supporters of different groups and political parties. The sounds of various revolutionary songs, Ali Shariati’s speeches, and the soundtrack of the Costa-Gavras films Z (1969) and État de siège (State of Siege, 1972) could be heard on every corner. The systematic and wide-scale attacks on dissident groups had yet to begin and the Bazargan government was still trying to reign in the post-Revolution chaos.

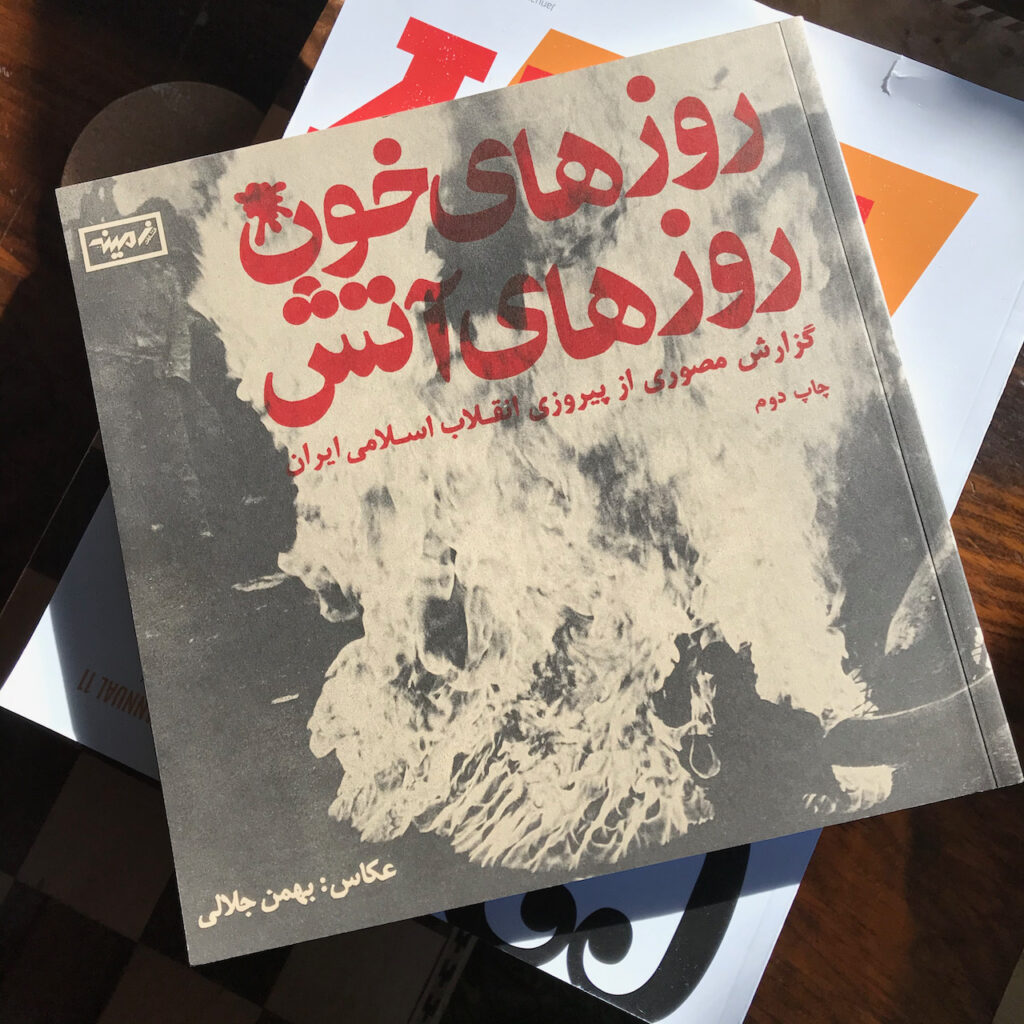

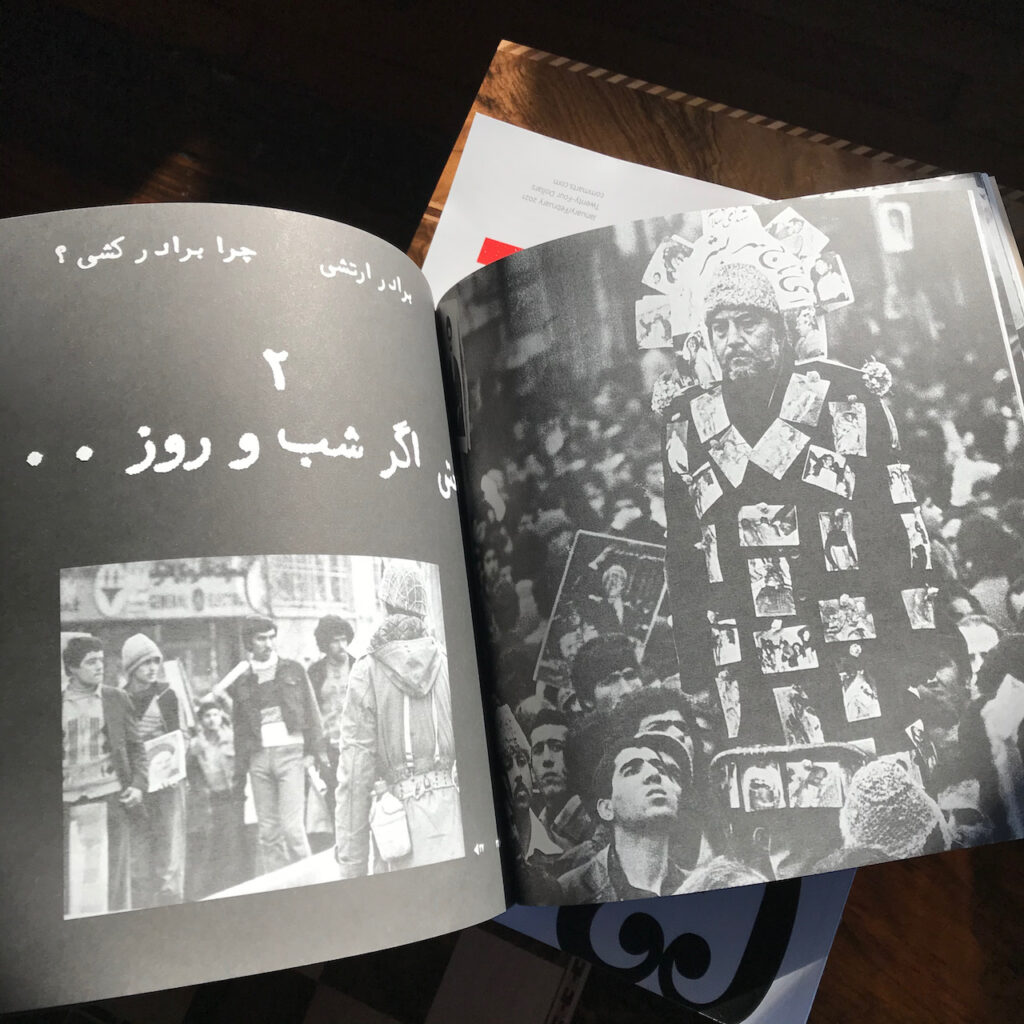

It was in such an atmosphere that the book Days of Blood, Days of Fire was published. I didn’t know the book’s editor, Bahman Jalali, but his name was etched in my memory that day. The book was not reprinted after 1979 as Iran’s new rulers viewed these photos as noncompliant with their official narrative of the Revolution’s history. After 1981, it was no longer possible to show the organizations and groups that had a hand in the victory of the Revolution and whose members were being executed en masse. A few years later, Jalali became my photography professor at university and I got to know him personally. When I was emigrating from Iran, I didn’t take the book with me, but throughout all these years, I always wanted to see the book one more time: perhaps to revive my childhood memories from the Revolution, perhaps because of its powerful photos, or perhaps, to some degree, in memory of Bahman Jalali.

I was recently able to find the book once again and purchase a copy of it that had been reprinted in Germany in its original size and format. The pictures that I was looking at with a new perspective years later appeared strange. The book is the same but the meaning is not. What were these photos telling me in those days? What are they telling me now? What are they not telling me? What was hidden from the audience then? What is hidden from the audience now, particularly those who know nothing but the official narrative of the Revolution?

Aside from the photos and a foreword written by Karim Emami, the book has no other text. The photos are accompanied by the revolutionary slogans people chanted during the era. Karim Emami admits that the book does not cover certain key moments of the Revolution. A few photos have been appended in order to add those moments he considers important to the book: Eid al-Fitr prayers 1979, the Black Friday massacre, and the Imperial Air Force technicians’ salute to Khomeini. But today, which one of those important moments represent the changes that occurred in the wake of the Revolution? Perhaps the meaning of this revolution should be sought in the things that were left unsaid: what was concealed, what was dismissed and overlooked, and what was too shameful to articulate.

The footage that disappeared

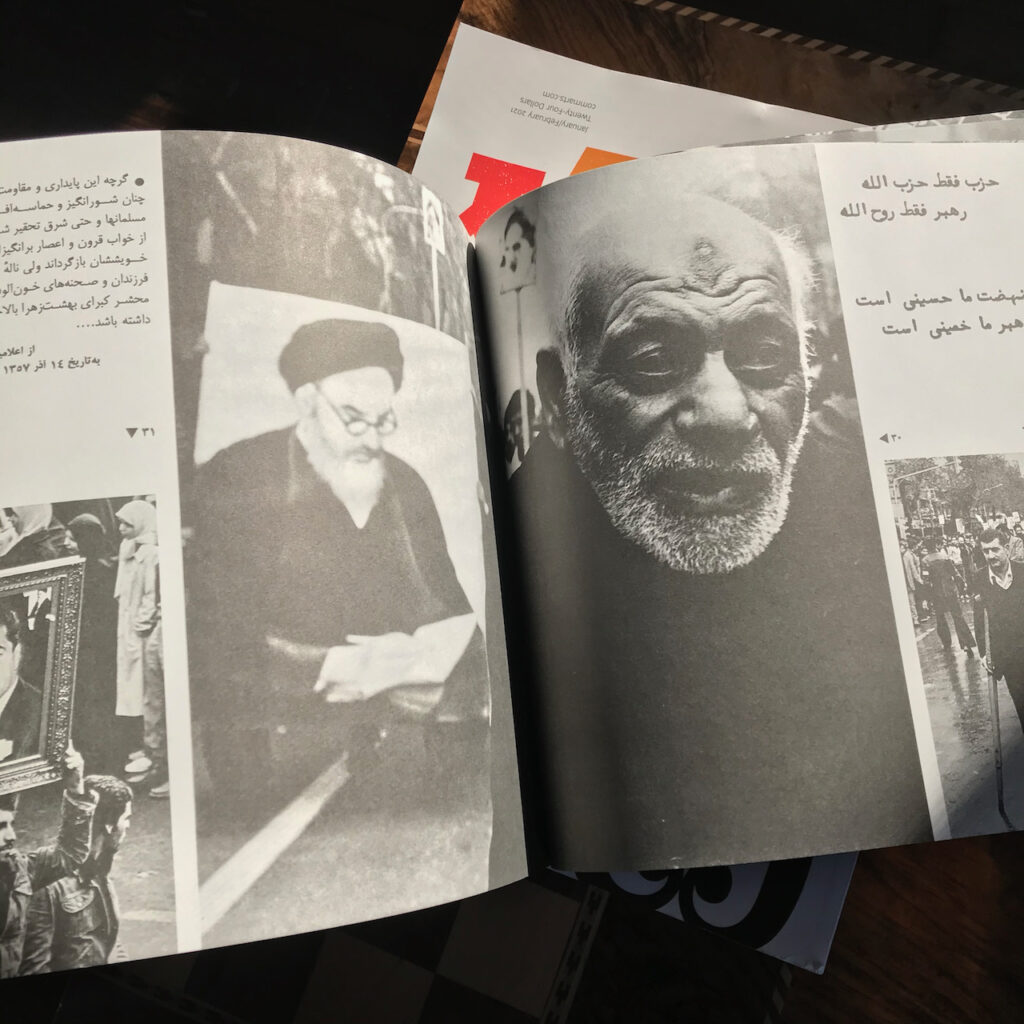

Photos from the day Khomeini returned to the country (headlines everywhere read “Return of the Imam”) show the Ayatollah among a circle of like-minded clerics and a group of religious intellectuals and reformists. Secular forces such as the National Front were not permitted anywhere close to him. In the documentary For Freedom (Hossein Torabi, 1979), Karim Sanjabi, the National Front’s leader, was shown among the spectators and not among the welcoming party. Socialist and Marxist leftists and the religious elements sympathetic to the left were not even allowed inside Mehrabad Airport. Today, one can easily discern who was of the inner circle and who was not. All were expected to form a united front for the victory of the Revolution, which called on everyone to stand in solidarity until further notice. But even in those days it was obvious which one of these groups had no place in the small circle of insiders. Few survived, even among the small entourage around the leader of the Islamic Revolution. The rest had either been imprisoned, fled the country, been assassinated, or forgotten from the early days of the Revolution. Those who remained to feast at the banquet on the spoils of the Revolution were often the unknowns, individuals such as Mohsen Rafiqdust, Khomeini’s young, obscure chauffeur on the day of his arrival. They decided which direction to take the Revolution.

In the photo of Khomeini deboarding the Air France plane, he appears surrounded by a group of his close associates: Morteza Motahari, who was assassinated a few months later; Ayatollah Lahouti, who was imprisoned three years later and who died in prison upon learning of his son’s execution; Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, who was executed on charges of attempting a coup; Sadeq Tabatabaei, who became persona non grata; and Abolhassan Banisadr, Iran’s first president, who was forced to flee to Paris after less than two years in office. Over the past four decades, images of Khomeini disembarking have been retouched and edited in a Stalinesque manner to keep the ever-shrinking circle of regime insiders content.

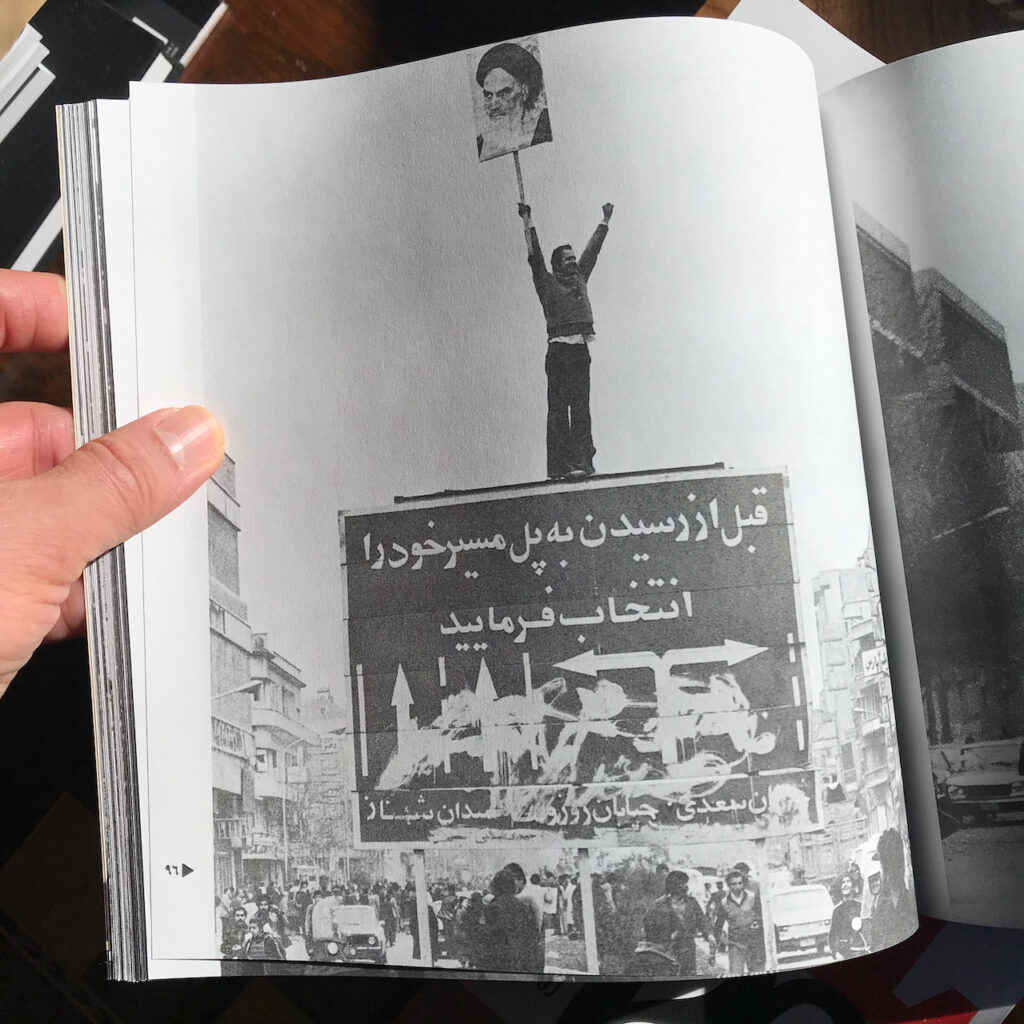

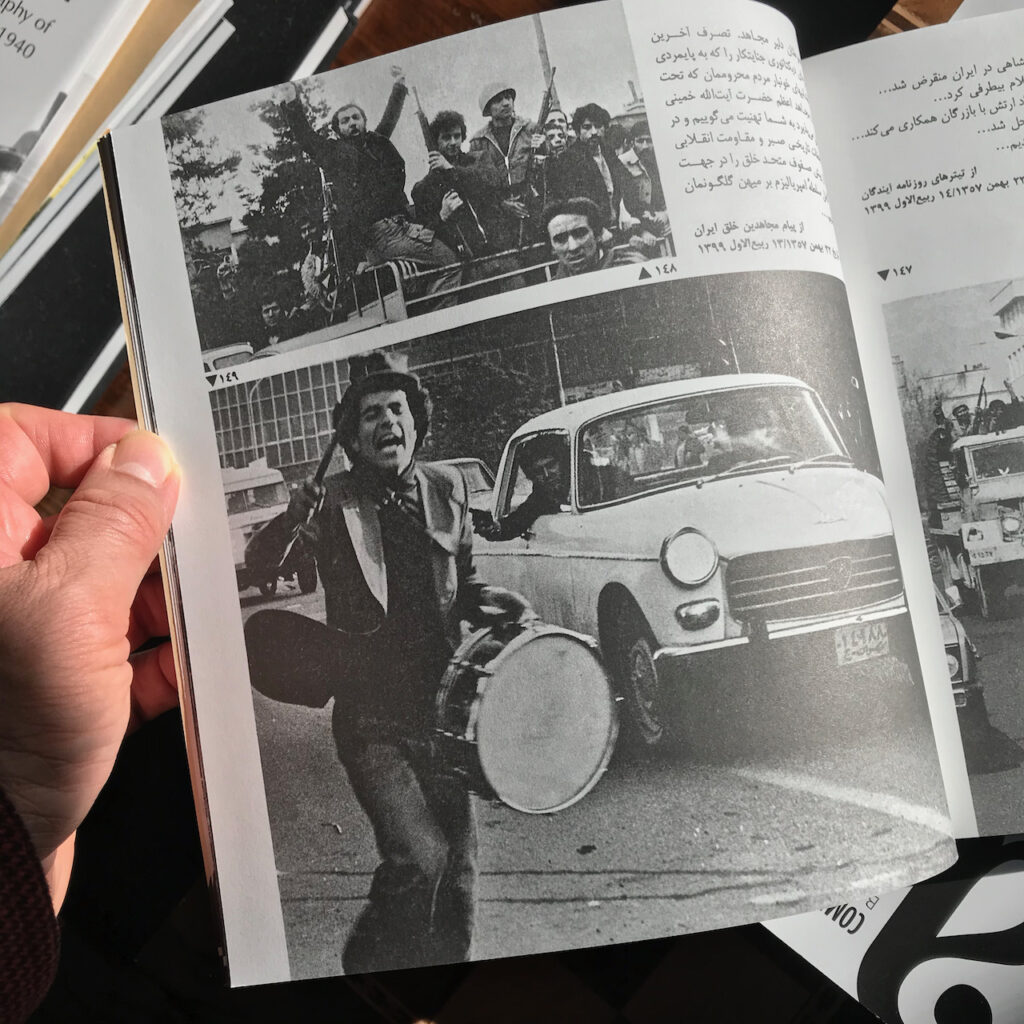

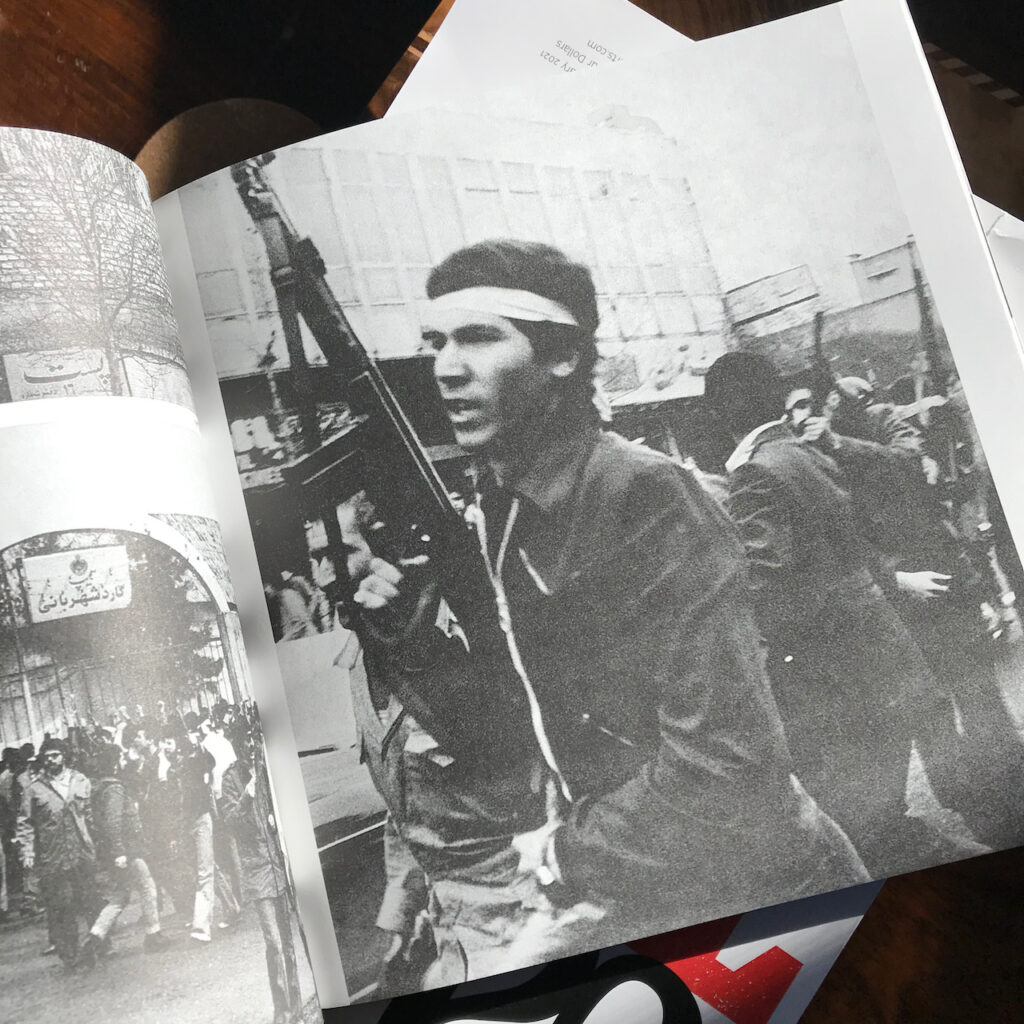

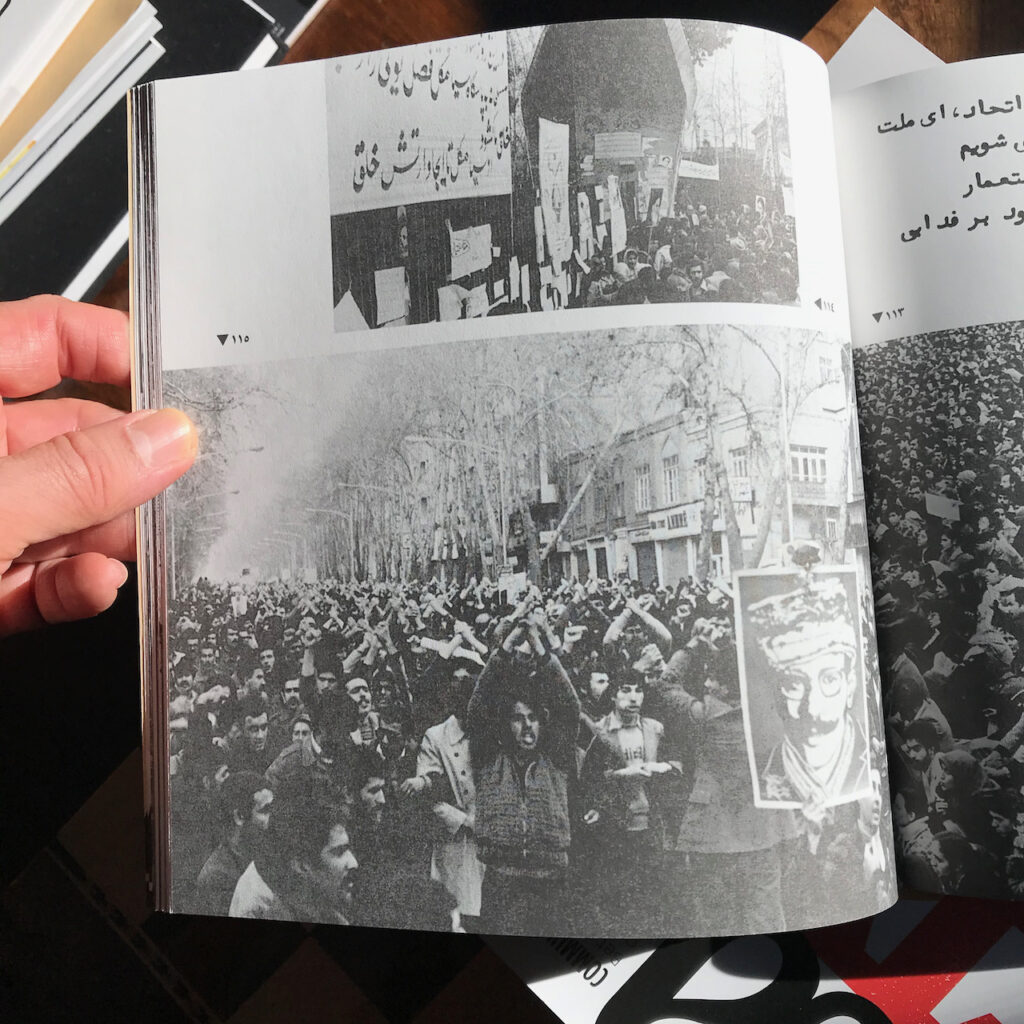

In Revolution-era newspapers and Days of Blood, Days of Fire, you can find the names of various political groups, and images of Ali Shariati and Mohammad Mossadegh are everywhere. You can even see the emblems of the People’s Mojahedin Organization and the Organization of Iranian People’s Fedai Guerrillas. Slogans and traces of the National Front, the Tudeh Party, and other political parties and groups are also visible here and there. In those days, particularly in the months leading up to the 1979 Revolution, everyone had accepted Khomeini’s leadership in order to overthrow the Shah. All of them were dropped from the official historical narrative of the Revolution. One can still find evidence of this systematic purge in newspapers and documentary films made immediately after the Revolution. In the film The Pulse of History (Asghar Fardoust, Davoud Kanaani, 1979), an Islamist activist reminds his followers that “our path and theirs is separate,” referring to the leftists. The Islamists can also be seen telling Marxists to refrain from using their own slogans. In For Freedom, a Marxist addresses the crowd bemoaning the shredding of folk hero Samad Behrangi’s photos. In another scene, an individual tries to convince a cleric that under revolutionary circumstances, everyone must unite, and “after this movement’s [victory], they can talk.” The cleric responds, “We have nothing to talk about.”

In the documentary The Footage That Disappeared (Hamid Jafari, 2010), the filmmaker searches through over 40 hours of lost raw footage, some of which was later edited to make The Pulse of History. Hours of footage about the release of 1,200 political prisoners on October 27, 1978 (a turning point in the Revolution) have disappeared. No footage of Ayatollah Taleqani, Safar Qahremani, and Gholamhossein Sa’edi shot by him and other filmmakers at Tehran University can be found anywhere. At two and a half hours long, The Pulse of History, made a few months after the Revolution, was whittled down from 40 hours of footage to create a specific narrative consistent with official portrayals of the Revolution at the time, though, once again, inconsistent with today’s official narrative of events. Events such as the arson at Shahr-e No (Tehran’s red-light district), where prostitutes were burned alive in their homes—among the forgotten parts of the Revolution—are depicted in The Pulse of History but absent from all other books and films. Why?

They did it

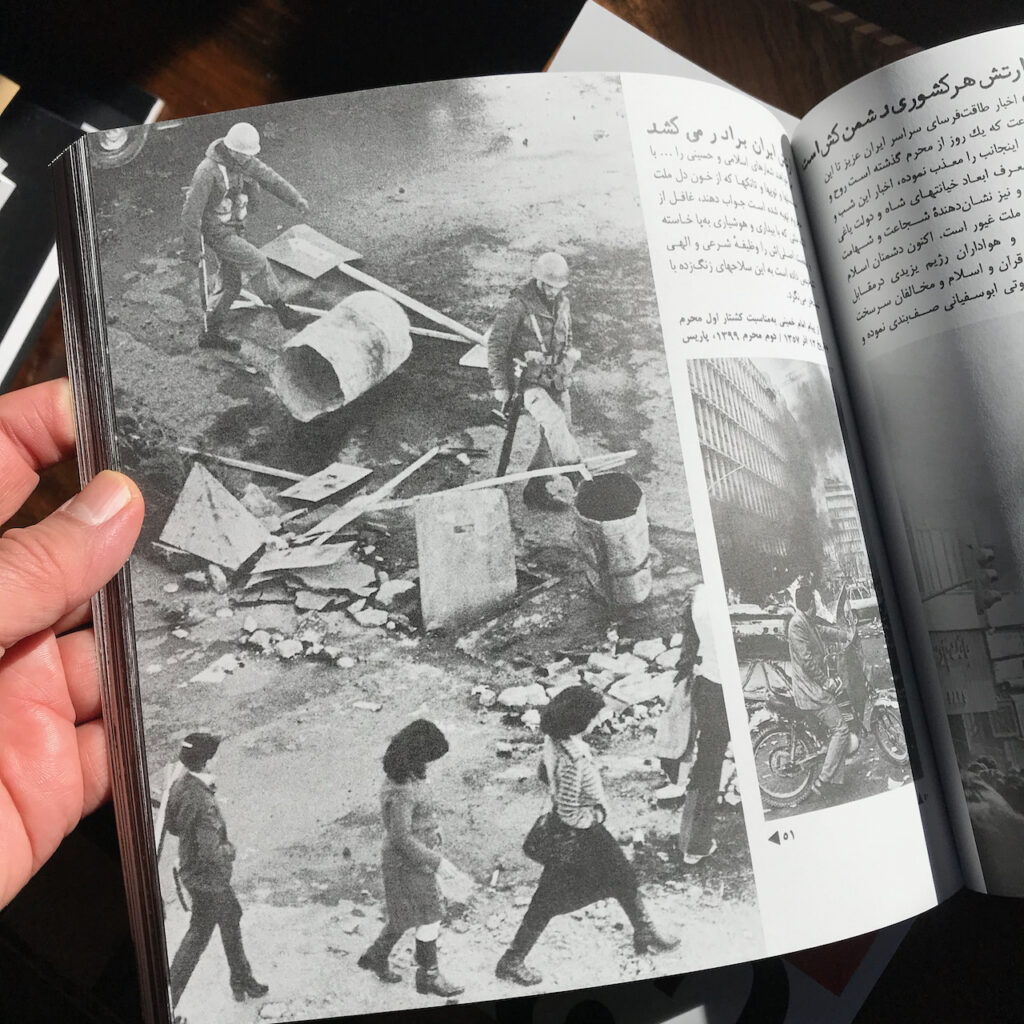

The 1979 Revolution manifested in mass protest and the burning down of banks, cafés, and cinemas. Why banks, cafés, and cinemas, you ask? There are those today who will not believe that the revolutionaries themselves started these fires. In the documentary 14 Aban, Day of Fire (Robert Safarian, 2008), the filmmaker sets out to find who set fire to banks and cinemas across Tehran on November 5, 1978. What I too remember is that the people themselves were setting fire to banks, cinemas, and cafés. There are those today who blame the Shah’s regime for these fires. Robert Safarian, who was present at the scene of a bank fire in 25 Shahrivar Square (7 Tir), recalls that the general perception on that day was that the protesters were responsible for the bank fires. But after seeing footage showing Capri Cinema (Bahman) burning while firefighters stood by, refusing to put out the flames, even he begins to doubt his own recollection and thinks perhaps the truth is different from that which he remembers.

On January 29, 1979, a group of protesters attacked Shokoufeh No nightclub, Shams beer brewery, liquor stores, cafés, and Tehran’s red-light district, Shahr-e No, setting them on fire. To show their support for protesters, firefighters announced that they would not put out any fire set by “the people who wish for it to continue to burn.” The homes of prostitutes burned to the ground and a number of them died in the fires.

The next day, Ayatollah Taleqani condemned these actions and labeled them as a plot by “the regime’s filthy mercenaries.” Images of the burned bodies of women were never printed in any of the photo books about the Revolution. The fires, like the one at Abadan’s Cinema Rex, were attributed to the regime. “They did it” rolled off the tongue of anyone who wanted to put the blame for these atrocities on the Shah instead of the actual arsonists.

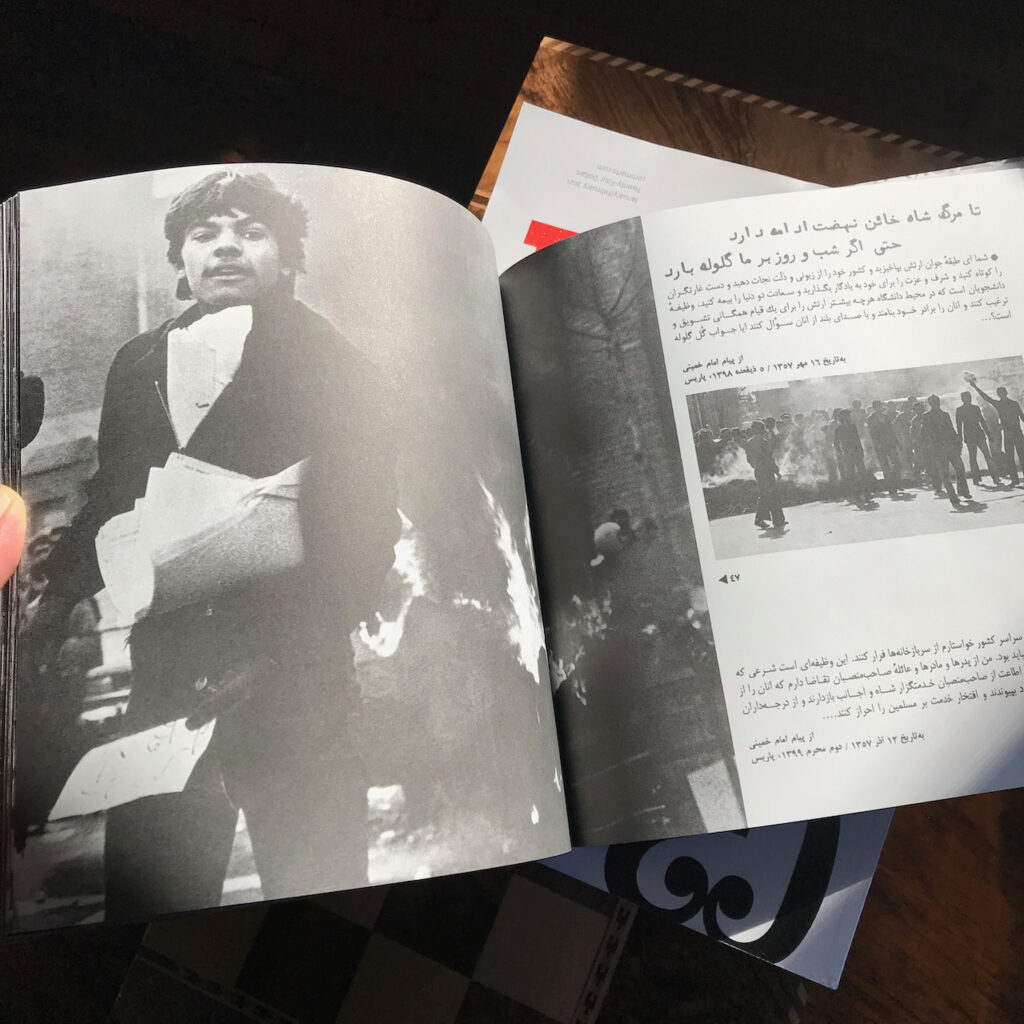

A few days later, revolutionaries brutally attacked another protest by supporters of Shahpour Bakhtiar. No images from those attacks were printed in any publication in Iran. In the documentary Abbas as Narrated by Abbas (Kami Pakdel, 2019), Abbas Attar, a celebrated Iranian photojournalist with Magnum Photos, says that, on that day, he was at the protest taking photos of revolutionaries attacking Bakhtiar supporters, but his Iranian friends and colleagues asked him to stop photographing and show his support for the Revolution. Censorship of the Revolution and the manipulation of its narrative began with the photographers who refused to snap the shots.

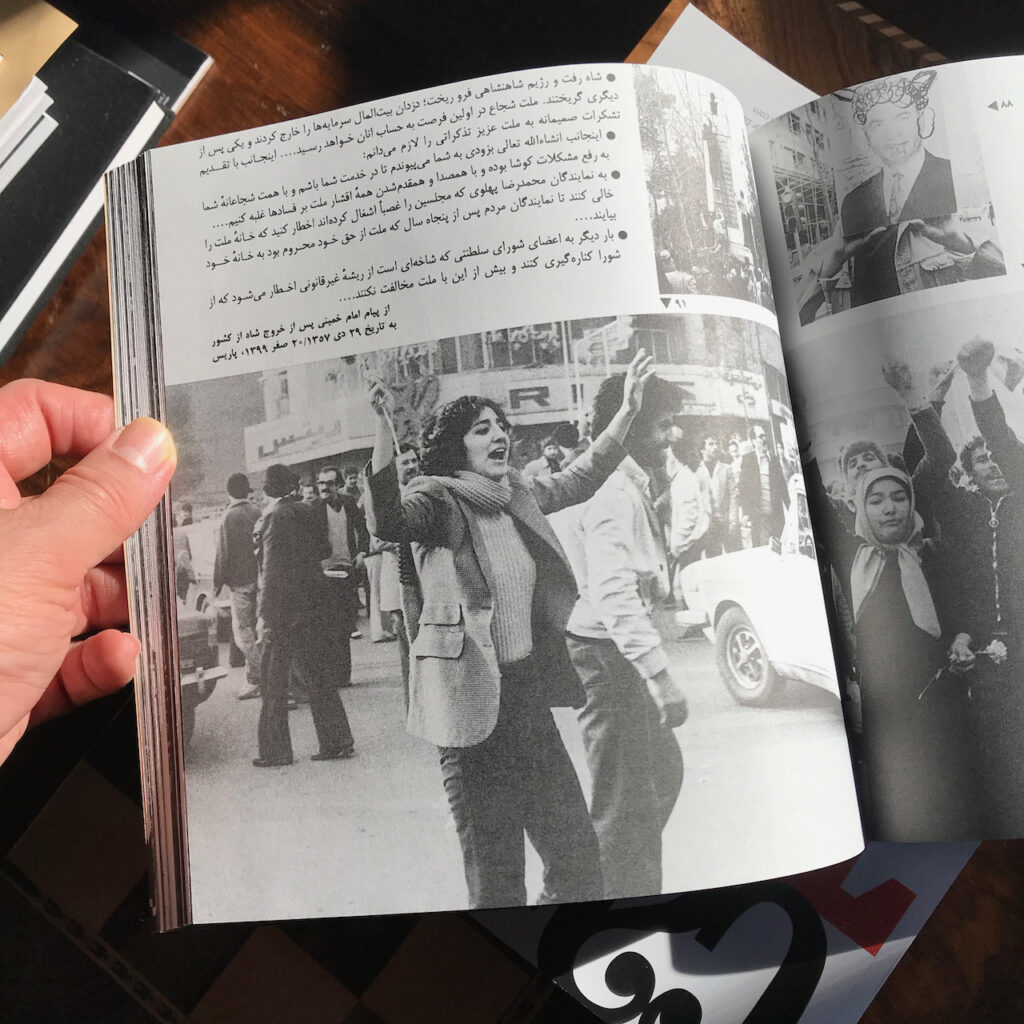

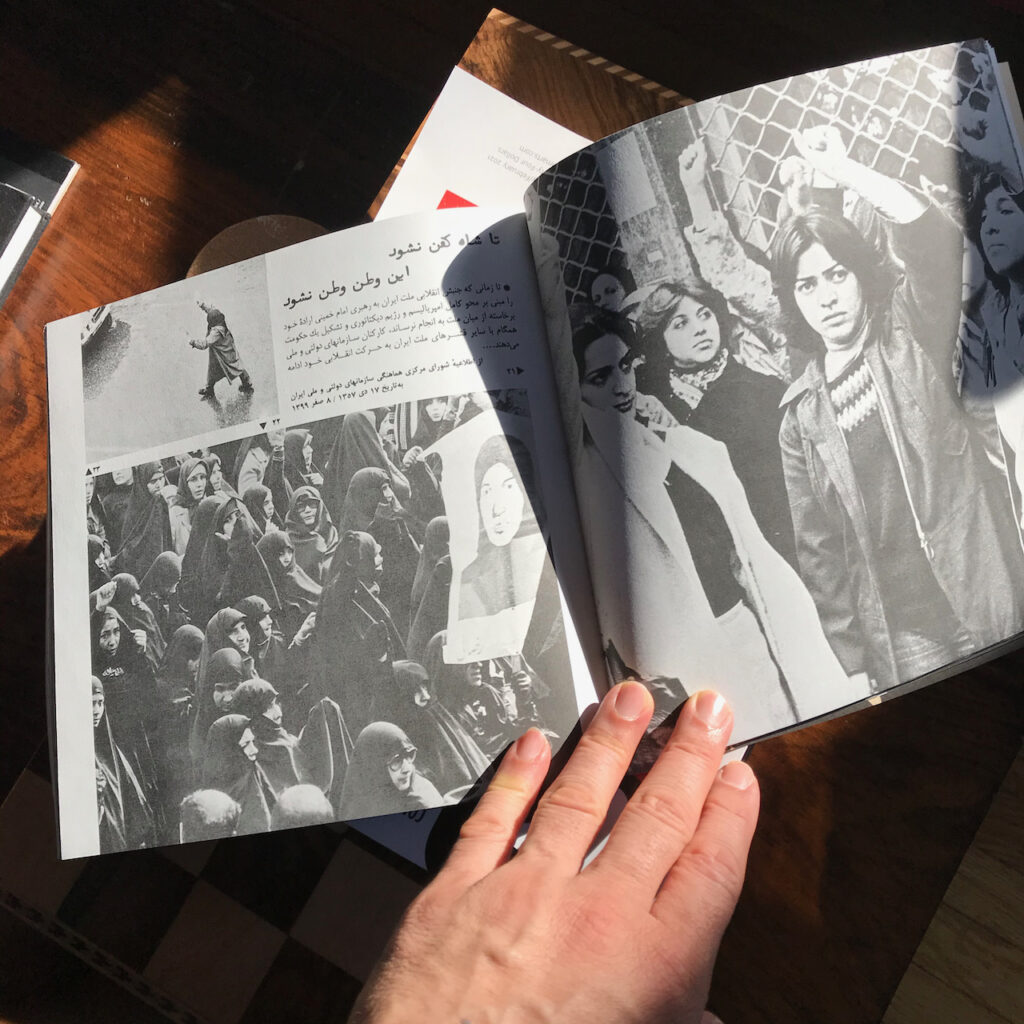

For me, the saddest photo in Days of Blood, Days of Fire is one by Rana Javadi of a group of women with clenched fists and no hejab. Among them is a woman whose silent rage has made her the focal point of the photo. I remember this photo from my youth. There was no shortage of women sans hejab who participated in the Revolution, and although their photos were later removed from the official narrative of the Revolution, this photo survived over decades. In the book, it appears alongside other photos of the Revolution, as if these clenched fists were raised in opposition to the Shah’s regime. As if these women without hejab were like the hejab-less, gun-toting, tank-mounting woman whose photo appeared on the front page of Kayhan to depict the victory of the Revolution. But the reality was something quite different: On March 8, 1979, less than a month after the victory of the Revolution, the women in Rana Javadi’s photo took to the streets to protest against the compulsory hejab and to demand their rights. These demonstrations received no support, even from the secular revolutionary organizations of the time. The photo has been taken entirely out of context, even in this book. It appears alongside photos of women clad in hejab demonstrating against the Shah. But perhaps this photo, more than any other one in the book, foretells of the devastation to come.

A bridge to the other side of “Bahman”

The victory of the 1979 Revolution, known as 22 Bahman, was no small-scale riot; it was a major revolution. It was an earthquake in both Iranian and world history. It was the end of an era, the end of the “short” 20th century.

Historians speak of “the long 19th century,” which started with the French Revolution in 1789 and ended with the opening shots of World War I in 1914. Perhaps one can say that the “short 20th century” began with World War I and ended with the Iranian Revolution, a revolution that resulted in a regime against human rights, against equal rights for women, anti-art, anti-diversity of thought among its people. The Iranian Revolution had a fundamental difference with other revolutions that have taken place in the past few centuries, from the French Revolution to the Cuban Revolution: The regime that emerged from the 1979 Revolution was the first revolutionary regime that shamelessly stood against modernity and the values of the Enlightenment. Michel Foucault, who spent time as a journalist in Iran during the Revolution, was one of the few thinkers who saw this fundamental difference in slogans and actions, despite misunderstanding them and naively placing hope in them. Others like Ahmad Shamlou, who at first viewed the Revolution as progressive and democratic, could see nothing but “a plagued haze” a few months later. This plagued haze spread to other countries in the region and swept through the world. January 1979 (the month of Bahman on the solar hijri calendar) was the beginning of a new era. Had Jalali envisioned the collapse of this avalanche? Perhaps. Maybe this photo which the book ends with is his implicit response to this question.

“Choose your destination before reaching the bridge.”